by Peter Rabinowitz, MD MPH

In 2015, the Rockefeller Foundation released a major report about the state of the planet, called Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch. This document outlines the case that anthropogenic changes in the environment are now threatening the basic life support services of the earth’s systems. Some of the concerning trends include biodiversity loss, climate change, particulate air pollution, ocean acidification, and deforestation. The report indicates a number of ways that this environmental degradation can pose a serious threat to human health in the future, and calls for urgent research and policy action to address these large-scale problems.

At the Center for One Health Research (COHR), we view these critical environmental threats highlighted by the Rockefeller Planetary Health Report as intrinsic to our understanding and application of One Health.

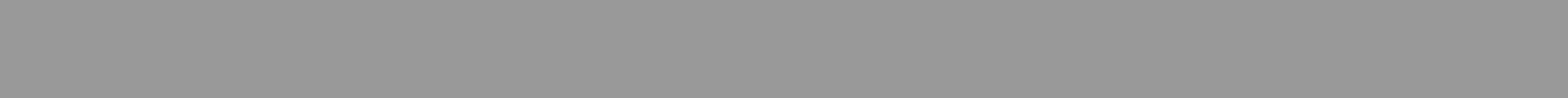

The COHR approach to One Health is to look at the interconnections between hierarchically organized systems of human, animal, and environmental health, as depicted in this figure.

Each domain of health: human, animal, and environment, can be seen as a system of increasing complexity, from the molecular level, up to the individual level, and higher to the community, and finally “planetary” level where global populations of humans and animals are interacting with biosphere forces, as detailed in the Planetary Health report.

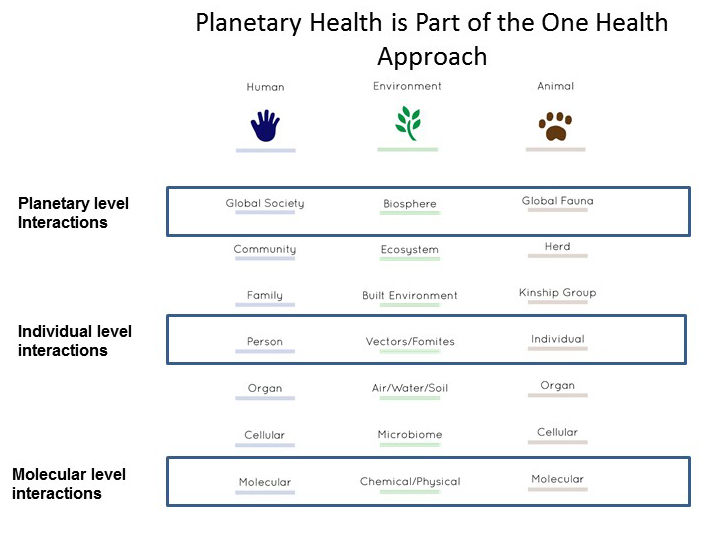

The utility of the One Health approach to planetary health is that it shows how interactions at simpler levels, such as emerging infectious diseases in individuals or small populations, can be connected to higher level interactions with environmental drivers such as climate change and deforestation. In the same way, an “animal sentinel event”, such as a sudden stranding of whales or other marine mammals, while sometimes traceable to a proximate cause such as a viral infection or a toxic exposure, may be telling us something about greater environmental forces at work, including the effects of an expanding human population.

This figure of interconnected human, animal, and environmental One Health systems, shows how an animal sentinel event at an individual or group level, can be scaled up to shed light on planetary level forces.

A key advantage to using the One Health approach to address large-scale health issues related to environmental change is that animal populations, like the canary in the coalmine, may be more sensitive to the effects of a changing environment. For example, the Rockefeller report mentions the paradox of human health indicators currently improving across the globe despite the many signs of environmental degradation. By contrast, the increase in animal disease outbreaks and extinctions is easier to connect to the environmental changes.

While many of the interactions between environmental forces and both humans and animals can be negative, One Health can also provide a model for sustainability of these interconnected systems. For example, a farm with animals, if managed in a One Health way that optimizes the health of the humans (both farmworkers and consumers and community members) as well as the animals and the local environment, can provide a scalable model that will go far toward mitigating the environmental consequences of large scale food production. One Health therefore goes “local to global”, or, more accurately, “molecular to planetary”.

We encourage our colleagues working on One Health efforts to consider how to establish clear linkages between smaller scale interactions they may be investigating (such as zoonotic disease outbreaks) and the larger issues of a rapidly changing, and not so healthy, planet.

Posted 5/15/17.