Caty Padilla, executive director of nonprofit Nuestra Casa, and Luz M. Fajardo, language program coordinator, give away masks at a drive-through event in Mabton, WA in August 2020. Photo: Courtesy of Nuestra Casa.

Community groups fill a public health gap for farmworkers and other Central Washington residents, new report from UW and Front and Centered shows

.jpg)

Community organizations in Washington’s agricultural heartland have met critical public health needs for farmworkers and other community members during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a new report by EDGE researchers at the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) and the nonprofit Front and Centered.

“We all suspected that community organizations were filling gaps that got bigger because of the pandemic,” said Esther Min, a former graduate student of EDGE member Edmund Seto and current DEOHS research consultant and environmental health lead for Front and Centered, who led the project. “This study showcases the breadth and depth of their efforts.”

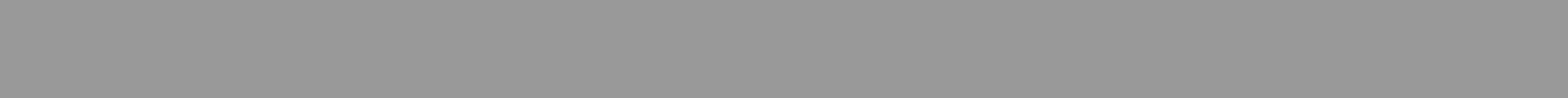

Last year, Nuestra Casa, a nonprofit serving immigrants in Washington’s Yakima Valley, organized drive-through events to distribute masks and information about the Washington COVID-19 Immigrant Relief Fund. Meanwhile, Wenatchee-based nonprofit Community for the Advancement of Family Education (Wenatchee CAFÉ) offered a food pantry and provided drive-up COVID-19 testing after a staff member was trained to give tests. The researchers gathered these and similar stories through interviews with eight community groups in Yakima and Chelan counties.

According to the study, some 68% of the community members the team surveyed in the region sought information from community organizations during the pandemic. The results underscore the importance of funding and supporting such community networks to prepare for future disasters. The project was funded by the UW Population Health Initiative.

“The organizations have almost had to serve as a pop-up humanitarian emergency relief response.”

- Aurora Martin

For the community, by the community

Farmworkers and other frontline communities in Central Washington already faced health inequities, economic insecurity and occupational hazards before the pandemic, said Aurora Martin, co-executive director of Front and Centered.

The pandemic amplified these challenges and added new ones, including getting accurate public health information amid language, culture and technology barriers; gaining digital literacy as schooling and many other resources moved online; and meeting basic needs, given the slow rollout of government support.

“Community-based organizations are key players for frontline communities, essential workers and particularly agricultural workers in Central Washington, where we saw a spike in exposure and even some deaths as a result of COVID,” Martin said. “When the pandemic hit, the organizations pivoted to provide humanitarian and emergency relief services.”

For the study, the team interviewed leaders from eight community-based organizations in Wenatchee and Chelan counties. Together, these groups serve over 250,000 people, including Latino communities, Spanish-speaking individuals, immigrant families, rural communities, agricultural workers and undocumented individuals.

The researchers, including EDGE member and DEOHS Associate Professor Edmund Seto, also received survey responses from 64 community members in these areas about their needs during the pandemic.

Sharing critical resources and tech training

The team found that community organizations provided food and financial assistance, shared information about COVID-19, distributed masks, facilitated COVID-19 testing and ran drives for school and personal supplies. They also gave trainings on how to use video conferencing, access applications for support services and support children’s online schooling.

Some organizations also teamed up to offer a “one-stop shop” of services. “One will do a school supply drive and then another will do a food drive, and then they'll partner with a health clinic to provide testing services,” Min said.

Organizations also advocated for community members to make sure local COVID-19 testing was free and accessible outside of typical working hours, Min said.

The results of the team’s survey of community members demonstrated widespread hardship in these communities, in which 84% of respondents identified as Hispanic, Latino or of Spanish origin.

All respondents reported at least one challenge during the pandemic including rent, job, food, worrying about COVID-19 for themselves or family, schools or accessing health care.

Supporting the support systems

The team’s results show the importance of engaging community organizations in the state’s vaccination campaign to ensure that vaccines are accessed and distributed equitably, Min said.

Some 40% of respondents to the team’s survey were undecided about getting the COVID-19 vaccine.

Some groups included in the study, including Spanish-language station Radio KDNA, are already sharing messages about vaccine safety and accessibility. The Washington State Department of Health recently launched a collaboration with community leaders to aid vaccination efforts.

Additionally, the critical support these organizations provide suggests that it is important to build their capacity, infrastructure and funding to prepare for future disasters like wildfires, Martin said.

“The organizations have almost had to serve as a pop-up humanitarian emergency relief response,” she said. “Imagine if they were able to coordinate and connect on a more ongoing basis, rather than pop up.”