Rural children with asthma whose homes have an indoor air cleaner are 72% less likely to have an unplanned clinic or hospital visit than children in homes with no air cleaners, according to a study from the University of Washington and partners in the Yakima Valley.

.png)

The study led by the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) tested whether children’s health and home air quality improved when they received portable home air cleaners combined with education on asthma triggers.

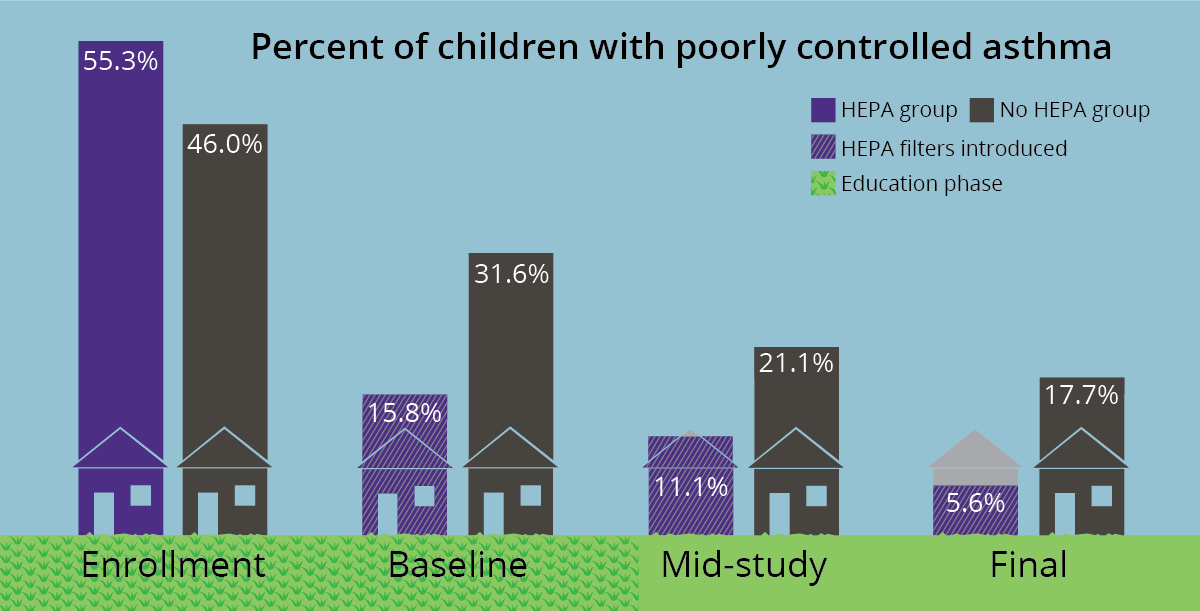

All children in the study received education from trained community health workers. But children who also received the air cleaners were 66% less likely to have poor asthma control than children in families who received education alone.

“The data show that these interventions work for patients and could save money by reducing the need for emergency care for asthma patients,” said Stephanie Farquhar, study co-investigator and DEOHS clinical professor.

One of the first to study rural childhood asthma

Asthma is often associated with cities and pollution from vehicles and industry.

But the children of farmworkers in rural Washington and beyond also experience asthma triggered by exposure to wood smoke, emissions from agricultural operations, harsh cleaning chemicals and other indoor air pollutants.

The Home Air in Agriculture Pediatric Intervention (HAPI) study, launched in 2014, is one of few studies to investigate rural childhood asthma and environmental factors. The just-completed study involved a research partnership between UW DEOHS, the Yakima Valley Farm Workers Clinic and Northwest Communities Education Center/Radio KDNA.

“This study is a great example of the impactful research that can be accomplished when academic researchers and community partners inform and participate in the research as a team,” said Dr. Catherine Karr, DEOHS professor and the study’s principal investigator.

Teaching asthma prevention and control

Researchers randomly placed 76 Yakima Valley farmworker families into one of two groups—those who were given a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) air cleaner at the beginning of the study and those who weren’t.

Seventy-one families completed the study, and those who didn’t receive a HEPA air cleaner were provided one when their study participation ended.

Children who participated in the study all had asthma and were between the ages of 6 and 12, all Latino or Latina and nearly all born in the United States.

All families received education and information on asthma triggers and medications at the beginning of the study as well as in-home visits by a community health worker. They also received an asthma prevention kit, including mattress and pillow dust mite covers and a green cleaning kit with non-irritating cleaning items.

Education helped—but air filters helped even more

“Health improved for all children in both groups with education and in-home visits,” Farquhar said, “but children in HEPA homes saw improvement above and beyond that.”

Researchers found that the percentage of children who reported asthma symptoms in the past two weeks was cut by about one-half for the HEPA group and by about one-third for the non-HEPA group.

About half of children in the non-HEPA homes had an unscheduled hospitalization or visit to a clinic or emergency room during the yearlong study. Just 11% of children in HEPA homes had unscheduled medical visits.

An unequal burden

Low-income children in Washington have asthma rates that are nearly 65% higher than children from higher-income homes. Farquhar said that ensuring low-income families have access to proven asthma interventions is a matter of health equity. It could also save the state money because the cost of emergency care is so high.

“When we find something that works, we need to figure out a way so that all families have access to proven solutions,” she said.

The HAPI study team is now sharing results with families and health officials in the Yakima Valley through community events and a new series of radionovelas, or radio dramas, that will play on local radio station KDNA.

The team recently shared findings at a conference hosted by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and has submitted research articles for publication in academic journals.