And like many fishermen, Kyle has close calls from time to time in Alaska’s Bering Sea, with wild weather and remote wilderness. Like the time a half-hour trip for firewood turned into a two-day, 30-mile trek home after their 24-foot skiff was swamped.

Still, Kyle doesn’t always wear a life jacket. “Once I’m getting to a point when I’m my dad’s age, that’s when I’ll have a life jacket on every day,” he says.

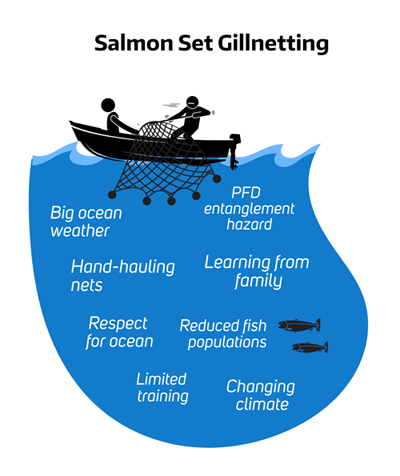

Research led by Leann Fay, Ph.D., recently gathered knowledge and lessons through interviews with members of this unique fishery to understand the factors that influence safety for setnet fishermen.

The research was conducted in partnership between Alaska Native community members and the Alaska Marine Safety Education Association (AMSEA).

“To be educated in marine safety is essential to fishermen as awareness can make all the difference in the world,” says Melanie “Mayugiaq” Sagoonick, a commercial salmon set-netter in Norton Sound for over 30 years.

“Out on the ocean, anything can happen, even with the most experienced fishermen. Being prepared in any given situation is crucial and is a matter of life and death,” Sagoonick says.

Recent reports from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health call commercial fishing one of the most hazardous occupations in the United States, with a fatality rate 29 times higher than the national average. The salmon set gillnet fishery has the highest number of fatalities in Alaska.

And fatalities for Alaska Native marine workers are on the rise. Ten out of 15 fatalities from commercial fishing vessel disasters in Alaska from 2010 to 2014 occurred in open skiffs, the type of vessel used in salmon set gillnetting.

Kyle remembers one early morning heading out from Norton Sound when “we knew what the weather conditions were like, but we still didn’t bring the life jackets. I don’t know why.”

His boat was 3 miles from shore in rough weather with swells between 5 and 7 feet. “We got out there and started pulling up the net. That’s when the boat started turning sideways,” he says.

“Well,” his dad said, “if anything happens, it’s too late now.” They focused on the nets, dragging up logs, king salmon and everything else.

“We don’t have a net roller – we have to pull it in by hand. When the bow came up, I was holding onto the net,” Kyle recalls. “When I let go, my hand got caught in a hole and started dragging me out.”

He was able to break free just in time, but the experience chilled him. “Just a couple more feet, and I was gonna be over,” he remembers. “If I went over with the net, I probably would have never been picked up. It’d be a pretty slim chance.”

Despite the need for emergency equipment like personal flotation devices (PFDs), it isn’t easy or inexpensive to ship the equipment to remote fishing villages in Norton Sound. Safety training for commercial fishing is not tailored for open skiff fishing nor for the unique needs and knowledge of Norton Sound’s fishermen.

AMSEA is developing a training for Native commercial fishers in Norton Sound to share research findings and distribute 30 inflatable PFDs with training and an assessment of PFD preferences.

“To share this knowledge through awareness and training is a wonderful start,” Sagoonick says. Research findings from AMSEA’s study will help improve awareness, promote solutions, and develop tailored training programs for this population and fishery.

Learn more about this project and other AMSEA projects at Pacific Marine Expo, November 17-19, in Seattle, WA. Expo visitors can try on a variety of PFDs designed for commercial fishing at an interactive table hosted by the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center (PNASH).

This project was funded by a pilot grant from the PNASH Center, part of the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences at the University of Washington’s School of Public Health.

To preserve the anonymity of research participants, a pseudonym is used for the young fisherman, Kyle.

Written by Sarah Fish who is a Graphic Design and Media Specialist for PNASH Center.