Right now, some 140,000 agricultural workers are picking apples, peaches and other crops at the peak of Washington’s harvest season, just as Gov. Jay Inslee has declared a state of emergency in response to wildfires burning across the state.

Agricultural workers are among those on the front lines of overlapping harvest and fire seasons while also facing exposure to extreme temperatures during summer heat waves. Yet little is known about how the combined effects of wildfire smoke and heat affect the workers who are essential to the state’s $10.6 billion agriculture industry.

New research is filling in some of those data gaps. A new study led by researchers in the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health (PNASH) Center pinpoints where and when farmworkers face the greatest health threats.

At the same time, PNASH is leading a related pilot project that will pair a statewide network of local weather stations with low-cost air-quality monitors to gather even more data about smoke to help protect both workers and crops. PNASH is part of the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS).

Where ag workers face the greatest risk

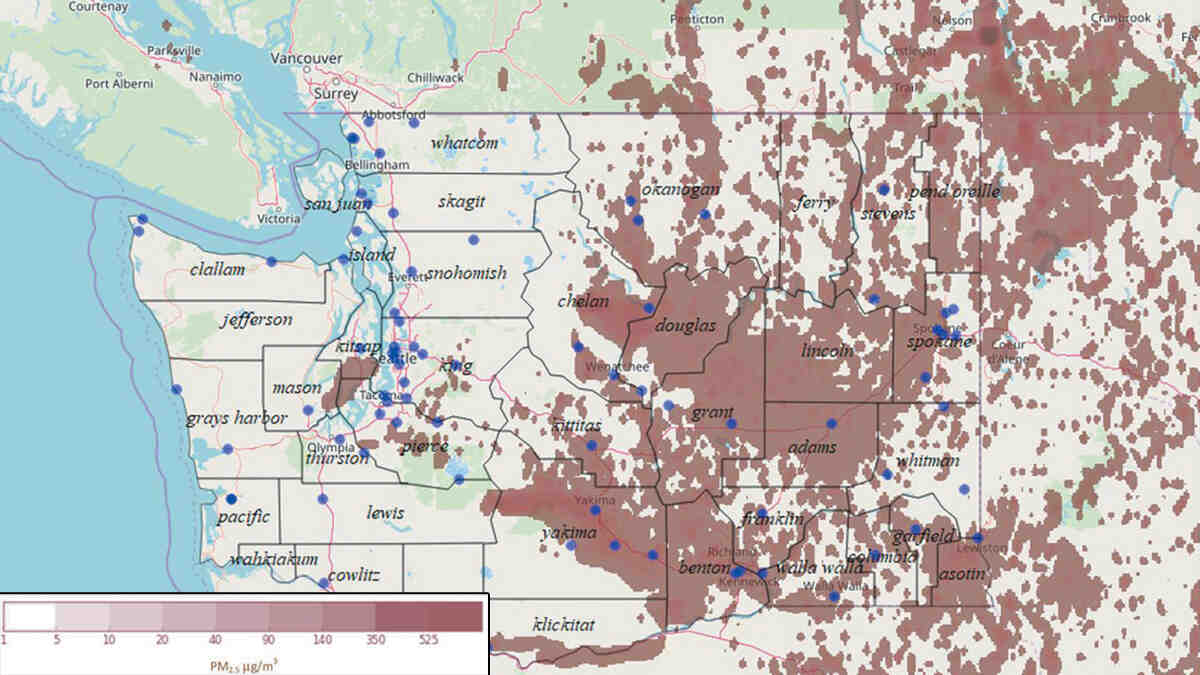

PNASH researchers set out to assess the combined effects of heat and tiny pollution particles called PM2.5 that are about 1/30th the width of a human hair.

“What we really wanted to know is how much impact is there on agricultural populations from wildfire smoke and heat together,” said Elena Austin, DEOHS assistant professor and lead author of a recently published study in the Journal of Agromedicine.

Austin and her colleagues found that Washington counties with the largest agricultural populations—including Yakima, Grant, Chelan and Benton counties—typically had the greatest concurrent high heat and PM2.5 exposures. These exposures tended to peak from July to September, when agricultural worker population counts were also highest.

The research team also found a mismatch between those counties and the availability of local air-quality information to monitor exposure to PM2.5 from wildfire smoke. Some rural counties with high agricultural populations have limited or no air-quality monitoring stations.

Another small PNASH research study recently found that nearly 3 out of 4 farmworkers in the Eastern Washington town of Mattawa reported being exposed to an unhealthy amount of wildfire smoke on the job, and 100% of respondents reported that they had little or no information about how to protect themselves from smoke.

Harvest season dictates working hours

“We know this population is particularly vulnerable to heat and particulate matter exposures because of their working and living conditions,” Austin said.

Another recent study led by UW and Stanford University found US agricultural pickers will see unsafely hot workdays double by 2050 because of climate change.

Austin noted that most agricultural workers work outdoors and have little control over their working hours and days because they must work when the crops are ready to harvest.

The combined health implications of heat stress and smoke exposure are substantial. Heat strain can lead to severe heat-related illness and death as well as traumatic injuries and acute kidney injuries. Exposure to wildfire smoke is associated with respiratory conditions and can exacerbate underlying asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Other co-authors of the research article are Edward Kasner, PNASH outreach director and DEOHS clinical assistant professor, and DEOHS Associate Professors Edmund Seto and Dr. June Spector.

Democratizing the data

Meanwhile, another PNASH team is leading the related pilot project, placing air-quality monitors on five of the nearly 200 existing weather stations maintained by Washington State University’s AgWeatherNet program.

PNASH is partnering with David Brown, AgWeatherNet director and WSU associate professor, and Scott Waller of Thingy IOT, a Bellevue-based sensor manufacturer, to deploy lightweight, power-efficient monitors made for remote environments.

By piggybacking on the existing weather station network, the new air-quality monitors could give growers and producers access to timely and highly localized data on air pollution, temperatures, humidity and other measurements to protect workers and crops during heat and wildfire events, Kasner said.

Claire Schollaert, a DEOHS doctoral student in Environmental and Occupational Hygiene, is helping to deploy the air monitors in Wenatchee this summer to test the idea by comparing data from the new monitors to data from other air-sampling equipment used by federal agencies to regulate local air quality.

“The dream for these low-cost sensors … is to deploy them across the state so that growers could pull data directly from an online portal to support precision agriculture and worker health and safety,” Schollaert said. “It’s like democratizing the data.”

Schollaert's faculty adviser is DEOHS Senior Lecturer Tania Busch Isaksen.

Author byline: Jolayne Houtz is DEOHS communications director.