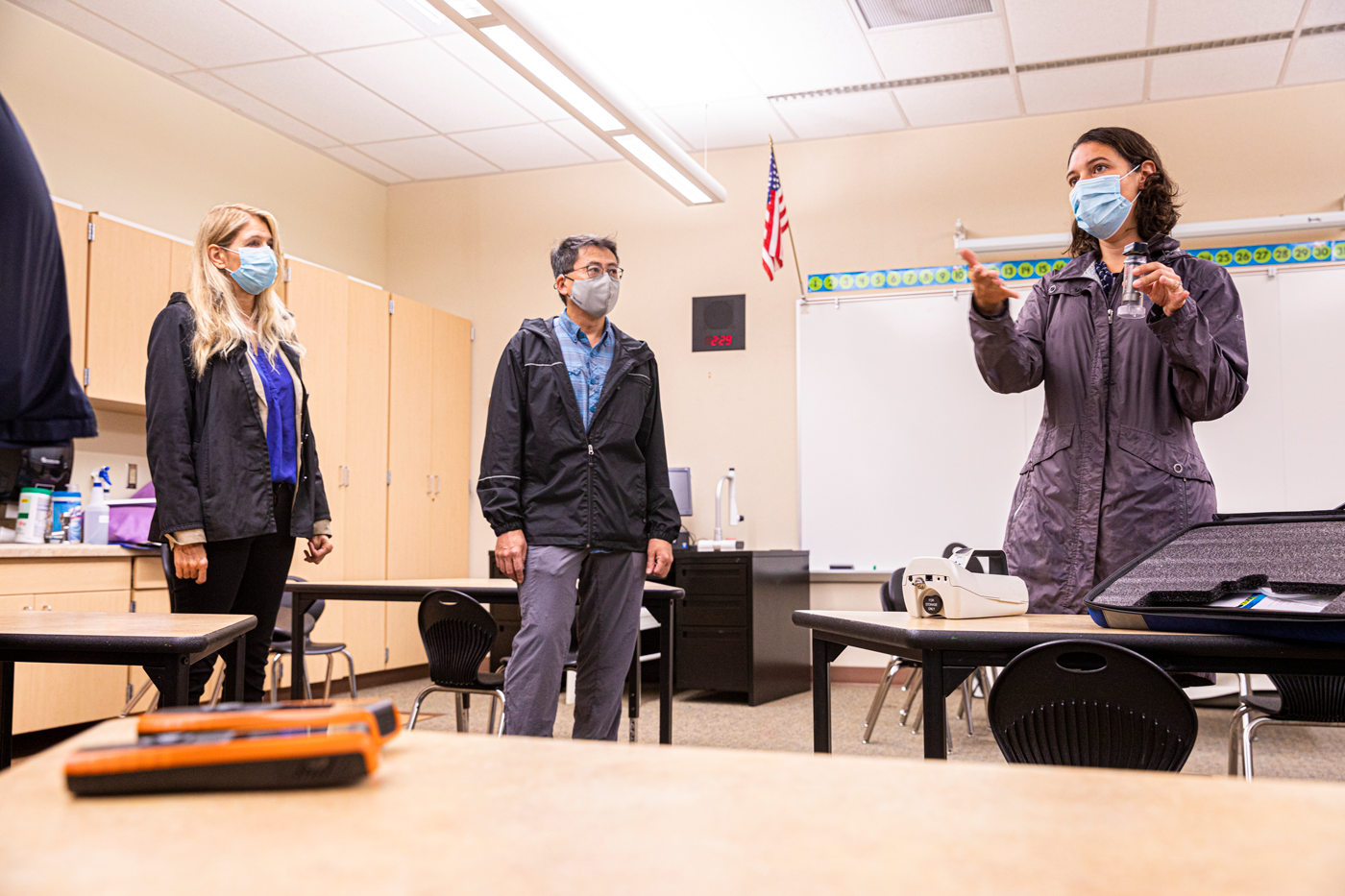

EDGE member Elena Austin is leading a project to track air quality in public schools near Sea-Tac Airport. Photo: Mark Stone.

Does ultrafine air pollution infiltrate schools near Sea-Tac Airport? EDGE researchers partner with cities in South King County to find out.

As students in King County public schools log into their online classes this winter, researchers from the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) are stepping into their temporarily empty classrooms to study air quality.

The UW Healthy Air, Healthy Schools project, led by DEOHS Assistant Professor and EDGE member, Elena Austin, is investigating whether ultrafine air pollution from jet and roadway traffic makes it inside schools near Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, and if so, what strategies are best for removing it to promote healthy indoor air.

“Ultrafine particles are an emerging health concern, and their outdoor concentrations are not currently regulated,” Austin said. “We want to evaluate the current indoor air quality situation in schools and see what could potentially improve it.”

The project, which focuses on five schools in the Federal Way and Highline school districts, is a partnership among the DEOHS team, the school districts, and the cities of SeaTac, Burien, Federal Way, Normandy Park and Des Moines. The research is funded by these cities and the Washington State Legislature, with support from state Sen. Karen Keiser (D-Kent) and Reps. Tom Dent (R-Moses Lake), Jesse Johnson (D-Federal Way), and Tina Orwall (D-Des Moines).

“It’s imperative we know which vulnerable populations are experiencing health side effects from poor air quality,” said Rep. Johnson. “With that information, we can identify where new filtration systems are needed to keep our children, teachers, and school staff safe.”

“What can be done?”

Communities around Sea-Tac Airport are exposed to ultrafine particle pollution distinctly associated with aircraft, according to a 2019 study led by Austin and other DEOHS researchers. Their Mobile Observations of Ultrafine Particles (MOV-UP) study, also funded by state lawmakers, was the first to identify the unique “signature” of aircraft emissions in Washington.

When people inhale these invisible particles—about 700 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair—the particles can pass from the lungs into organs, including the brain. Ultrafine pollution particles have been associated with negative effects on respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological health.

School-aged children could be especially vulnerable to some of these health impacts, and research suggests that air pollution could influence academic performance.

When the MOV-UP team presented their findings to members of communities surrounding the airport, “the question we got most often was, what could be done about it?” Austin said. In the discussions that followed, the researchers and their partners hatched a plan for the new school study.

“The UW research on ultrafine particulates that are produced by burning jet fuels has sparked renewed concern about the air quality for the children and adults living in airport communities,” said Sen. Keiser. “Thanks to the work of the UW research group, we now have the data we need to take action. Finding the best method to improve the air quality in schools is a crucial first step toward healthier communities.”

Real-time air quality monitoring

Starting this month, Austin’s team is using portable instruments to monitor the concentration of particles of different sizes inside and outside the five schools. The team also includes DEOHS Associate Professor and EDGE member Edmund Seto and Professor Timothy Larson.

By measuring air quality indices including carbon dioxide, relative humidity, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide and black carbon, they will also determine the particles’ likely sources, such as roadway traffic and jet pollution.

Then they’ll evaluate the impact of two interventions to improve air quality inside schools:

- Using a portable HEPA air purifier in the classroom.

- Working with school maintenance staff to examine possible improvements to schools’ heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

The team’s preliminary tests in classroom visits last fall showed wide variability in how ultrafine particles infiltrated different schools. Surprisingly, Austin said, the trends didn’t seem to relate to the age of the building or HVAC system.

The team plans to report their results later this year. They will also communicate their findings with families and community members in the two school districts, an effort led by DEOHS PhD student Nancy Carmona.

Targeting equity and environmental health

“The communities surrounding the airport tend to have more individuals who are lower income, have more Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) individuals, and also tend to have higher exposures to environmental health hazards,” Austin said. “So there is an equity issue in terms of who may be exposed to air pollution in our state.”

These concerns extend to communities in central and eastern Washington, which are hit hard by wildfire smoke and other sources of air pollution.

“This project will give us a better understanding of the air quality in our schools, especially with the increase in wildfire smoke our state has experienced the last few years,” said Rep. Dent, who represents the Moses Lake area. “The health and well-being of students, teachers, and staff is just as important as providing a quality education.”