What if a simple oral swab could help eliminate a disease that kills nearly 2 million people every year?

That’s the premise behind an international effort led by researchers in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) that could revolutionize the way tuberculosis (TB) is diagnosed.

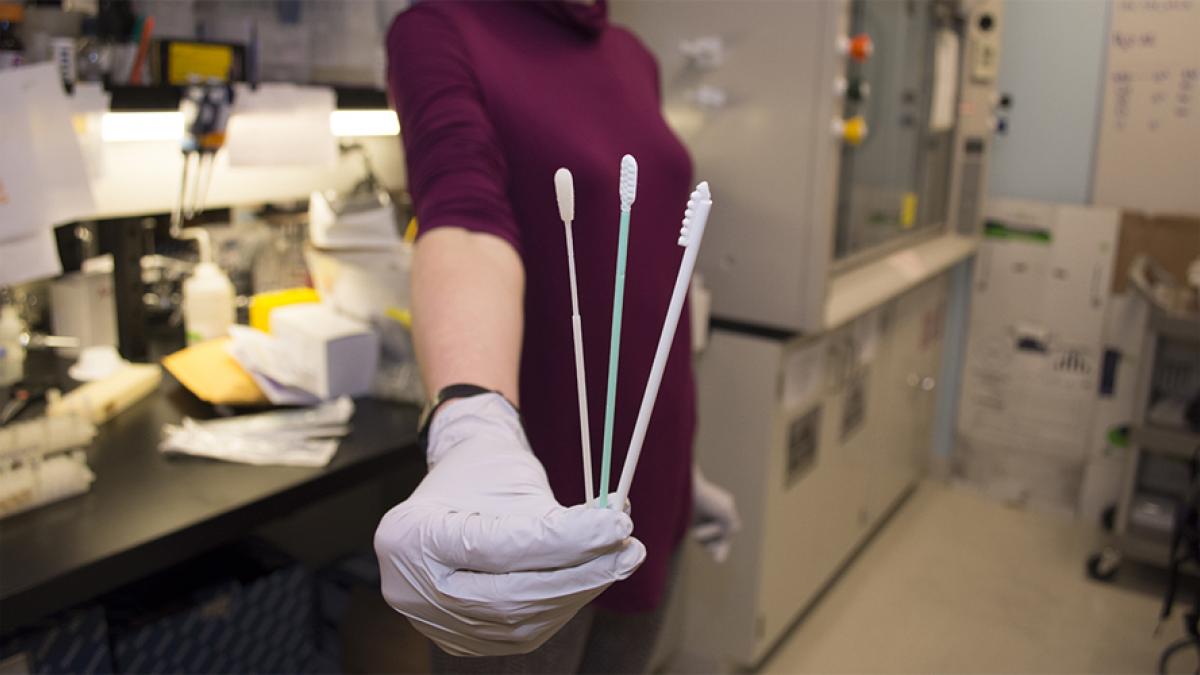

Using cotton or polyester swabs to collect bacteria samples from the mouths of patients for diagnostic testing could allow health care providers to test more people more quickly at lower cost than existing methods—and get patients into treatment faster.

This promising approach just got a sizeable funding boost from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, raising hopes that it could become part of the global strategy to end TB by 2030.

Early testing, treatment is critical

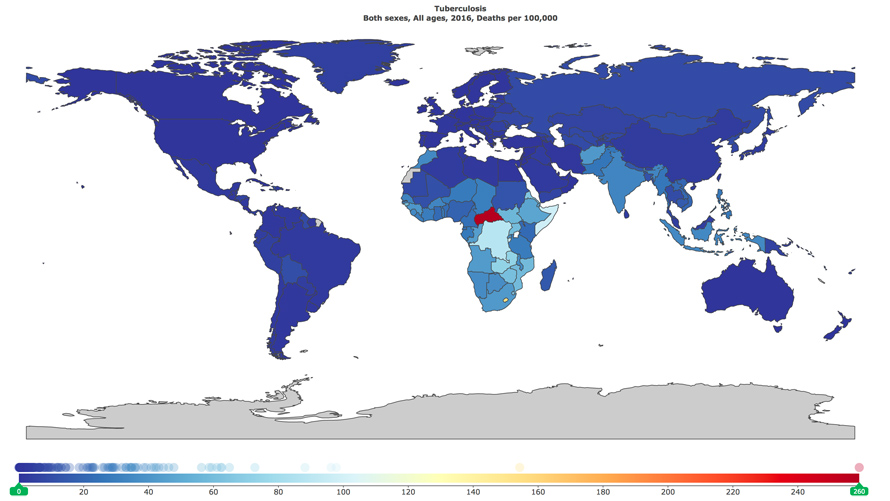

Early diagnosis and treatment is key to reducing the spread of TB, which killed 1.7 million people in 2016, including 210,000 children, according to the World Health Organization.

“With TB, there’s a week where you think you have a cold,” said DEOHS Professor Gerard Cangelosi, who leads the research study. He is also an adjunct professor of epidemiology and global health in the UW School of Public Health.

“Then the second week, you think it’s really awful. And the third week, you realize you’re dying, and you go get diagnosed with TB. During that interval and until you begin treatment, you are highly contagious,” Cangelosi said.

The Gates Foundation announced today that Cangelosi’s team was awarded a $100,000 Grand Challenges Explorations grant to support continued development of the oral swab diagnostic method and research into how samples can be collected, stored and transported.

Low-tech innovation

So how could the decidedly low-tech swab—a medicine-cabinet staple invented nearly 100 years ago—transform the global fight against TB, the world’s top infectious disease killer?

First, let’s talk about sputum.

The worst job

To test for TB now, a health care worker gathers a sample from a suspected TB patient who coughs up thick, mucousy sputum from the lungs. Many health workers say collecting sputum is the worst part of their jobs, Cangelosi said. “It freaks them out.”

Workers are at risk for exposure to the disease when patients cough. Collecting samples from children is especially hard because health workers have to make children gag until they produce enough sputum for testing.

And the substance is hard to work with—even trained laboratory technicians can have difficulty identifying TB bacteria when looking at sputum samples under a microscope.

From monkeys to humans

In 2012, Cangelosi began an unlikely collaboration with Lisa Jones-Engel, a UW anthropologist who approached Cangelosi about a technique she was using in her veterinary research to sample for TB in monkeys.

She was using swabs to collect bacteria samples from inside the cheeks of monkeys--a simple, non-invasive technique that allowed her to accurately diagnose TB.

Could the same method be used in humans? Much of the TB research community was skeptical.

“Nobody believed her, but I believed her,” Cangelosi said. “I was trained as a bacteriologist. You scrape surfaces because all bacteria like to stick to surfaces. That’s where they live.”

The oral swab method

The human version of the test involves a 10-second swab of the tongue or cheeks—no coughing or sputum required.

Samples are then analyzed for the presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Earlier research showed that researchers using the oral swab method correctly detected TB in most adult participants with the infection.

Rachel Wood, a DEOHS research scientist, began working on the project with Cangelosi as a DEOHS graduate student. She remembers Cangelosi initially describing the work as “high risk, high reward.”

Since then, she and lab teammates have analyzed nearly 2,000 TB samples collected by research collaborators in South Africa. Wood still gets excited when she finds positive samples. “To have it all coming together, with this being proposed as an alternative diagnostic test, is really amazing,” she said.

Next: proving it

This is the second round of Gates Foundation funding for the project, which was initially launched with seed money from DEOHS.

The next step is critical: showing that “everything you can do with sputum you can do with swabs,” Cangelosi said.

That means you have to be able to collect, store, transport and test samples in a way that yields results at least as accurate as the sputum method.

“To have it all coming together, with this being proposed as an alternative diagnostic test, is really amazing.”

- Research Scientist Rachel Wood

TB testing in schools, prisons

Many TB researchers are trading their skepticism for cautious optimism that this innovative approach could help reduce the global burden of TB, he said.

It’s also an example of the potential impact of increased collaboration between human and veterinary medicine. DEOHS is home to the Center for One Health Research, which investigates the links between human, animal and environmental health.

If the oral swab method is validated as a new diagnostic tool, the biggest impact could be in large institutional or community settings where TB can spread quickly from person to person.

“If you want to sample an entire prison or school or garment factory, you can’t get sputum samples from such large populations,” Cangelosi said. “But you can do it with oral swabs.”

Other UW DEOHS research collaborators include the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative and the University of Cape Town, South Africa.