Terrance Kavanagh

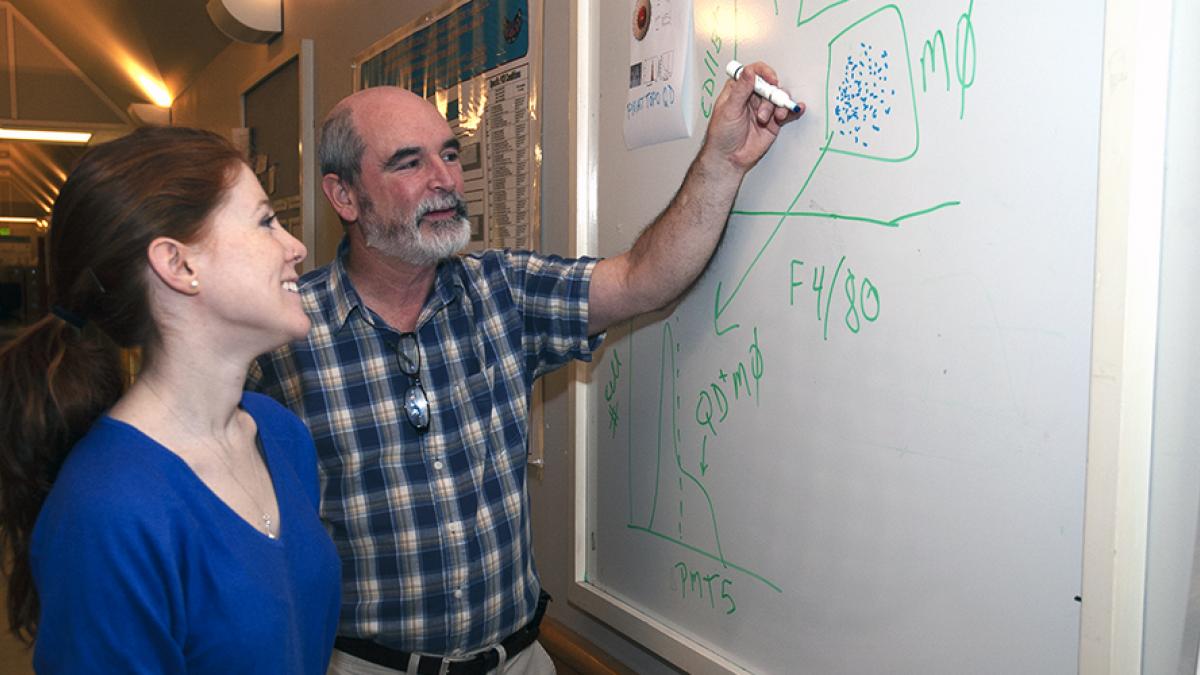

Professor, UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences

Adjunct Professor, UW Departments of Medicine and Pathology

Director:

UW Interdisciplinary Center for Exposures, Diseases, Genomics and Environment and the UW Nanotoxicology Center.

Co-director, the Predictive Toxicology Center

Joined DEOHS faculty:

1989

“Studying environmental toxicology and genetics was a way to combine my interests in environmental sciences . . . and health, letting me contribute to both environmental and public health.”

- Terrance Kavanagh

Terrance Kavanagh, professor in the University of Washington Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences, is one of two UW researchers recently named among the 416 new fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Fellows are elected by peers in recognition of their efforts to advance science or its applications.

Below, we talk with Kavanagh, 64, a laboratory scientist, fly fisherman and winemaker who left his native Michigan for the UW in 1985 to become a postdoc in the pathology department. Today, he directs or co-directs three UW centers. His comments have been edited for clarity and length.

What work are you most proud of?

We were among the first to create cellular and animal models (lab mice) of modified glutathione synthesis. This work is important for understanding which individuals are most susceptible to harmful environmental exposures, as well as for understanding human diseases and our metabolism of drugs.

Plants, animals and humans all produce the antioxidant glutathione, which lessens harm from exposure to toxicants and disease conditions associated with oxidative stress. As humans age, glutathione levels drop. But a person’s genetics also affect how efficiently the body replaces the antioxidant as it is expended to protect our cells.

We’ve modified a gene in lab mice so that they can no longer efficiently make glutathione. This lets us probe the role glutathione plays in many cellular and physiological processes.

We can then relate those processes to common genetic differences in humans that give us variable capacity to make this vital antioxidant—and, therefore, variable levels of vulnerability to suffering adverse health impacts from chemical exposures.

What in your wide-ranging work has most impacted human health or the scientific field?

Our work can be used to understand who is most vulnerable to toxic chemicals and under what conditions, informing environmental and public health policies that aim to protect susceptible individuals within the broader population.

This is especially useful as personalized medicine and precision environmental health policy evolve.

We already know low glutathione in animals is associated with negative cardiovascular effects from diesel exhaust. In humans, low glutathione can predispose us to acetaminophen drug overdose and resulting liver damage. And we know glutathione dysregulation is linked with cerebral vascular disease, metabolic syndrome, cystic fibrosis and Type 1 diabetes.

Researchers across the country have used the models we (and others) have developed to investigate the importance of this antioxidant in protecting cells, animals and people from various drugs and chemical pollutants and to explore aspects of development and aging, cancer, liver, lung and kidney diseases, inflammation and immunity, psychiatric disorders and neurological diseases.

Tell us about the timely e-cigarette research you’re doing.

Our work with the National Cancer Institute will investigate the potential carcinogenic effects of e-cigarettes—and not just around nicotine.

Important questions relate to the huge diversity of flavoring agents used in these devices. We don’t know a lot about these agents’ toxicity and their ability to initiate and promote precancerous lesions or even cancer itself.

Flavoring agents can turn into reactive aldehydes that can change your DNA. This is the Wild West: People are putting in all kinds of flavoring—and it’s largely unregulated. What happens when these flavoring agents get heated up? Is second-hand exposure to exhaled vapors, particles and chemically modified elements from e-cigarettes potentially harmful? Are we genetically predisposed to susceptibility for adverse effects from e-cigarettes?

We’re using genetically inbred strains of mice that are predicted to be more (or less) susceptible to these e-cigarette constituents. Hopefully this will let us discover, through genetic mapping, those gene variants associated with susceptibility (or resistance) to e-cigarettes.

What drew you to your field? With an undergraduate degree in natural resources, you’ve gone from the natural world to the world of the body and how the first affects the second.

Yes, I’ve gone from studying the entire environment to cells in a dish. I spent a lot of my childhood in the woods and waters of Northern Michigan, which gave me a sense of wonder about the natural world and inspired a love of science.

Today, I hike and camp at Mount Rainier and fly-fish the Yakima River and rivers in Montana. I started college in premed, but found myself also drawn to ecology, evolutionary biology and natural resources. I realized that studying environmental toxicology and genetics was a way to combine my interests in environmental sciences with my interests in medicine and health, letting me contribute to both environmental and public health.

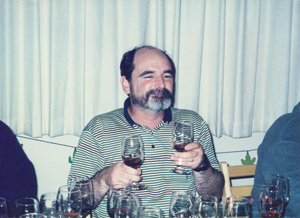

You’ve got a reputation as a quality winemaker who shares the (literal) fruits of your labor at department get-togethers. Are your forays in fermentation just another form of lab play?

I’ve been fortunate to have wonderfully fun colleagues and friends as fellow winemakers for almost 20 years. Each year seems to have its unique qualities of season, climate and timing. The strains of yeast and malolactic bacteria we add all impact our wines’ quality, which gives us a lot to discuss and argue over.

Naturally, this also requires frequent sampling as the wine ages.