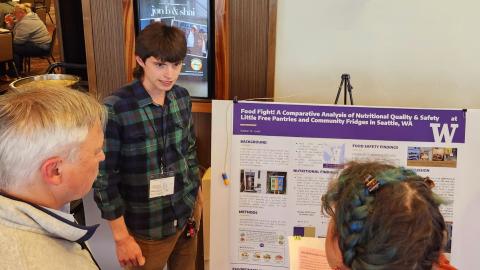

One afternoon this fall, UW faculty member Emily Hovis and two of her students visited a publicly accessible, outdoor refrigerator at St. Joseph Parish in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. It’s part of a network of similar resources in the Seattle area run by the mutual aid group Seattle Community Fridge.

Like the one at St. Joseph, many of these fridges are accessible 24 hours a day for the public to take and leave food. They represent a resource that has become even more critical with recent threats to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) program that many people in the U.S. rely on for basic nutrition. There are hundreds of similar sites around the world run by nonprofits, mutual aid groups, congregations and individuals, according to the community organization Freedge.

Hovis, an assistant teaching professor in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS), studies these community fridges as well as micropantries, unrefrigerated sites for sharing shelf-stable food.

Through surveys, she has found that people who use these resources often have barriers to obtaining traditional food assistance — they might need a source of food they can walk to, or have trouble getting to a food bank when it’s open because of their work hours.

“This is a type of food sharing that seems to be growing, and I anticipate it will continue to grow given federal reductions in spending for our traditional hunger relief sector,” Hovis said. “We found that the majority of people who are using these sites are both donors and receivers.”

Making community food sharing safer

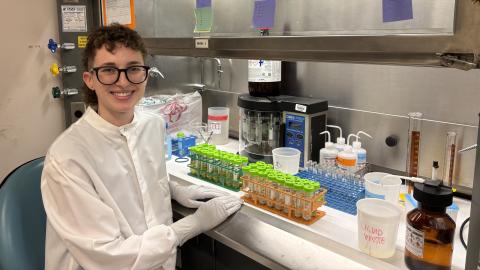

As a former food regulator for the Washington State Department of Health, Hovis also wants to make sure the food in these community fridges is safe. Recently, she teamed up with UW’s Urban Freight Lab and many other partners in a pilot project to help the sites run more efficiently and safely using smart sensors.

“This is a way for neighbors to feed their neighbors, and I think it is a really great thing,” she said. “It’s important to make sure we can do that safely so everyone is happy and healthy.”

The project, led by Anne Goodchild and Giacomo Dalla Chiara of the Urban Freight Lab, also includes Marie Spiker, a faculty member in the Department of Epidemiology, Food Systems, Nutrition and Health, and DEOHS; as well as the Allen School, the company Ridwell, Cascade Bicycle Club, the University District Food Bank, the nonprofit Sustainable Connections, and the Washington State Department of Health. It is funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation.

.jpg)

“Micropantries are a decentralized way of helping with people’s food needs while also ensuring that good food doesn’t go to waste, all in a hyperlocal context,” Spiker said.

Smart sensors

In partnership with Sustainable Connections, several sensors will be installed at community fridge sites in Whatcom County, including a scale and a temperature sensor whose data will be publicly available. Vikram Iyer, assistant professor in the Allen School, is leading the sensor development and deployment.

Volunteers already check the fridges for spoiled food when they restock them with food from local food banks. The scale allows users to remotely monitor the weight of food in the fridge, helping them know roughly when it’s time to restock, when items might go bad, and whether food is available for pickup.

The temperature sensor notifies users when a fridge is not keeping food at a safe temperature so that the food can be discarded and the fridge repaired. Community fridges are often placed outdoors, where they are more vulnerable to the elements, pests or vandalism.

“Because they’re decentralized, it’s hard to know whether a micropantry is full or empty, or whether a community fridge is at a safe temperature,” Spiker said. “The sensors and information dashboards this team is developing will go a long ways towards helping us understand the potential of micropantries to reduce waste and distribute food safely at a community level.”

Food insecurity in rural communities

The Sustainable Connections partnership offers a unique opportunity to explore community refrigerators in both urban and rural areas of Washington state. The nonprofit operates “freedges” at the RE Store in downtown Bellingham and at two more rural sites: the North Fork Library in Maple Falls and the Upper Skagit Library in Concrete.

Such remote monitoring could be particularly beneficial in rural areas where a community fridge is often a long drive for fridge users and restockers, and where there are limited resources for food assistance, Hovis said.

“We have higher rates of food insecurity in our rural communities than we do in our urban communities,” she said. “Thinking about how to design efficiency into these community systems is the goal of the project.”

Hovis’s team plans to do regular safety assessments to see how food safety varies between fridges with and without data dashboards.

Coming out of the grey zone

When it comes to food regulations, community fridges currently operate in a “grey zone,” Hovis said.

Her ultimate goal is to help develop a set of standards for them in collaboration with community members and the Washington State Department of Health. She and her team plan to convene focus groups with community fridge operators and other hunger relief organizations around the state to understand how best to include these resources in the state’s food code.

“How can we enable this type of food sharing while making sure there are safety standards in place to make sure the people receiving the food are not going to get sick?” she said.

She also plans to create a fact sheet outlining acceptable donations: for example, store-bought canned food is welcome, but home-canned food is not.

“Foodborne illness does not discriminate,” Hovis said. “Just because food is donated does not mean that it is safe.”

Understanding community needs

Spiker is leading the social science aspects of the project, including surveys and focus groups to learn about the experiences, motivations and behaviors of people who use micropantries.

“Some people donate food to micropantries, some people receive food, and some do both. The human element is really important; you can develop these great new technologies, but people may use those technologies in unexpected ways,” she said.

“Understanding who’s using micropantries, and how, and why — these insights complement the rest of the team’s expertise in transportation engineering, wireless sensing and food safety.”