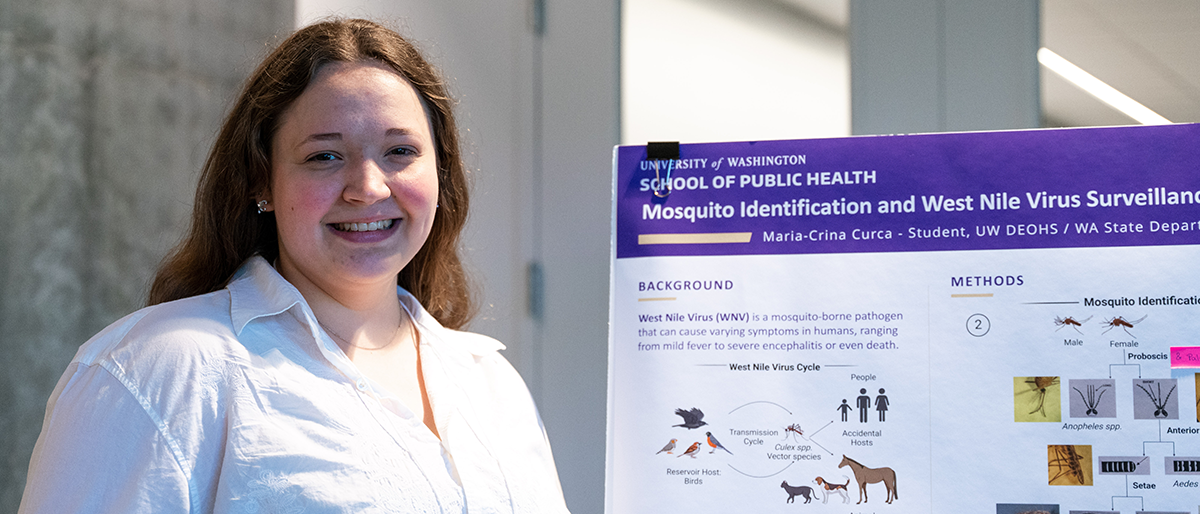

Maria-Crina Curca

What is your project focused on?

During my internship at the Washington State Department of Health, I focused on mosquito identification and West Nile virus surveillance in Washington state.

To accomplish this, I engaged in the meticulous task of individually sorting mosquitoes based on their species-specific physical characteristics. We received mosquitoes from 18 different locations across the state with the aim of identifying the only two species capable of transmitting the virus in our state: Culex pipiens and Culex tarsalis.

For virus surveillance purposes, we employed biochemical assays such as RNA extraction and RT-qPCR. These techniques allowed us to determine the presence or absence of the West Nile virus in the mosquitoes and assess the levels of viral activity, if present. Throughout the internship, I personally sorted approximately 25,000 mosquitoes.

DEOHS Professor Scott Meschke was instrumental in bringing this opportunity to my attention via DEOHS academic adviser Janet Hang. I am grateful to all those involved in making this experience possible.

When you look back on this experience, what will you remember as the most interesting thing you learned?

Firstly, I gained knowledge and practical experience in diverse areas, including testing marine water for coliforms, specimen handling under the microscope and conducting my first independent RT-qPCR.

Additionally, I acquired fascinating facts that expanded my understanding. For example, I learned that female mosquitoes are the only ones that bite humans, which explains why our carbon dioxide traps mainly capture female mosquitoes. I also discovered that Legionella bacteria can exhibit chain-like features under the microscope after Gram staining.

Moreover, I realized the significance of networking and how multiple career paths may help you get the dream job—there is no specific path to be followed!

I also became aware of the differences between working in the public sector versus academic laboratories and gained insights into different career paths, which is very helpful for junior scientists like me.

However, given that mosquito identification was the primary focus of my internship, I take pride in my ability to recognize certain mosquito species even without a microscope. I have even developed an affinity for a particular mosquito species in Washington, Culiseta incidens. Additionally, I can teach others how to differentiate between female and male mosquitoes without magnifying devices.

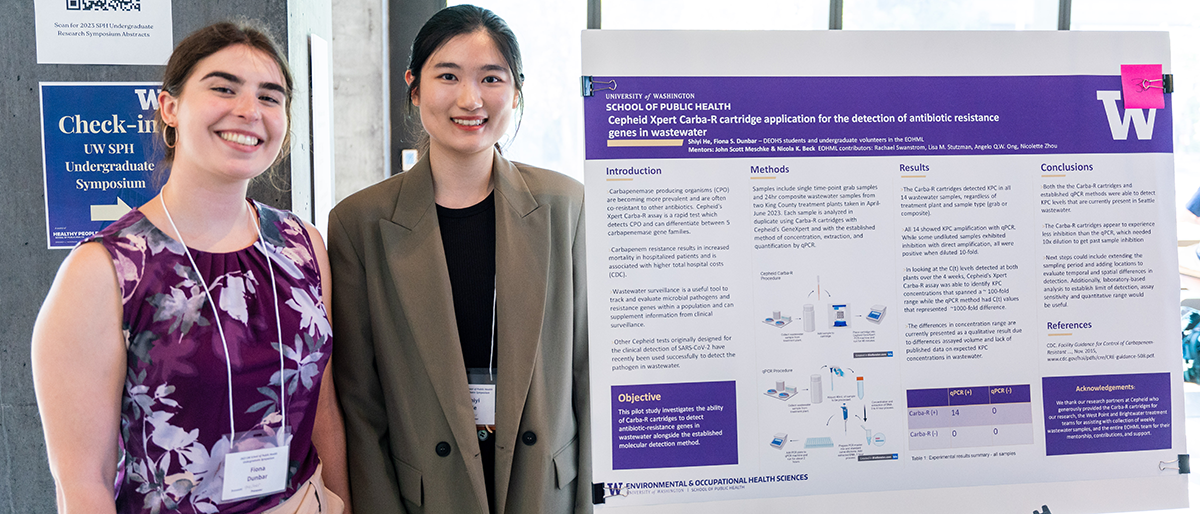

Shiyi He and Fiona Dunbar

What is your project focused on?

Our research project investigated whether Cepheid Carba-R cartridges, which are a very fast and simple method of PCR (a method used amplify DNA), could be used to detect antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater. These cartridges are currently only used in the clinical setting.

Other Cepheid cartridges for detection of SARS-CoV-2 have been used successfully in the lab we volunteer in with DEOHS Professor Scott Meschke in the Environmental and Occupational Health Microbiology Lab, so we decided to see if the Carba-R cartridges would work also.

When you look back on this experience, what will you remember as the most interesting thing you learned?

What I found most interesting throughout the process of this project is how much we do not know. Everything we learned just brought up more questions. There are so many ways we can expand on the research we have done so far.

We were able to detect our target antibiotic resistance gene in all of the wastewater samples. I am curious to know if detection would be different in a rural setting with fewer hospitals and other medical facilities.

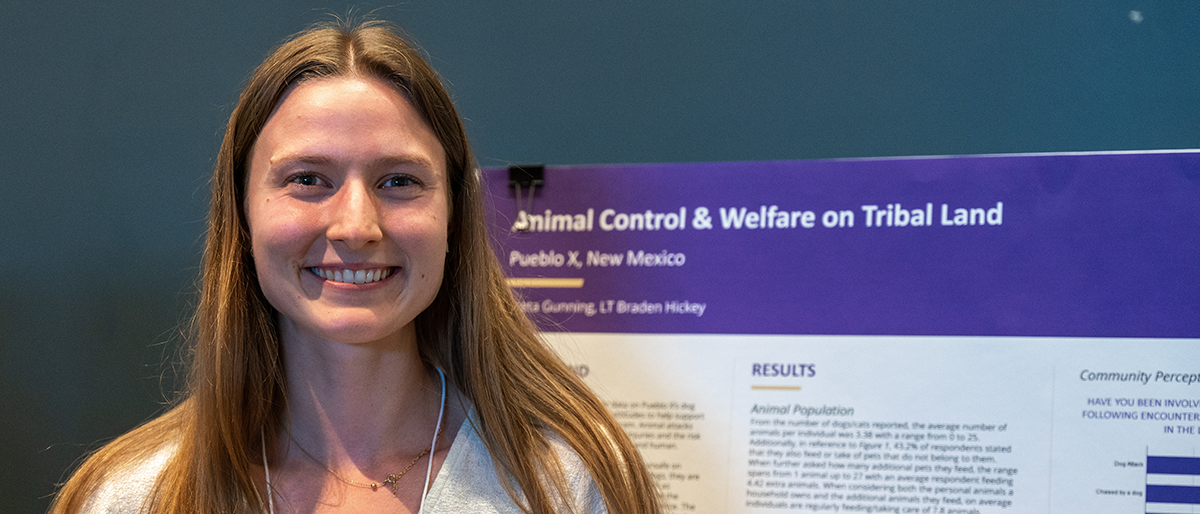

Greta Gunning

What is your project focused on?

My project is focused on animal control and welfare on tribal land, specifically in Pueblo X (X is used for the pueblo's privacy). I conducted this project during my internship with the Indian Health Services in New Mexico. The goal of this project was to gather data on Pueblo X's dog and cat population and perceived community attitudes to animal control within the pueblo.

Animal control and welfare was currently a major topic in Pueblo X due to the lack of an animal control program. Community members had expressed concern over their safety both due to physical injuries from dogs and the potential exposure to rabies.

When my mentor first discussed the option for this project with me, I was taking the Zoonotic Diseases class taught by DEOHS Assistant Teaching Professor Emily Hovis. As a result, the animal control option felt like a great opportunity to apply concepts I was currently learning in class to a real-world issue.

When you look back on this experience, what will you remember as the most interesting thing you learned?

When I look back at this project, one of the most important lessons I will take away is that individuals are eager to voice their concerns, however they need to feel supported and listened to in order to do so.

One of the challenges I first encountered in my project was reaching my target number of survey responses from the community. I had been mainly distributing surveys through online community forums and through Pueblo members at various locations throughout the pueblo.

However, I was not receiving the number of responses I expected. I had to reevaluate my distribution plan, and I ended up going door-to-door to distribute surveys as well as passing them out myself during a free spay and neuter clinic.

By doing this, I was able to have one-on-one interactions with community members and people were much more willing to tell me their problems when they saw that their comments were being listened to and acknowledged.

At the free spay and neuter clinic, individuals were also able to visualize the services which could be provided through their participation in the project, incentivizing them to provide honest and critical feedback.