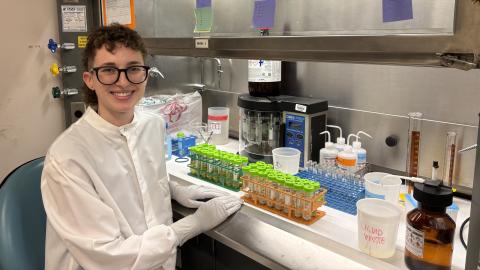

Even before she became a public health researcher, Rebekah Petroff was thinking like one.

Rebekah Petroff

PhD

Hometown

North East, PA

Future plans

A postdoc in human epigenomics at the University of Michigan, and a future academic career.

“ The great thing about toxicology is that it allows you not just to answer what is causing health effects, but also why. And so it gets way down into the nitty gritty, but it’s also applicable to everyday life.”

- Rebekah Petroff

Petroff grew up in North East, a small town in the far northwest corner of Pennsylvania known for its grape farms. She remembers learning from her mother, a nurse, that the town had a particularly high rate of autism. She wondered if the farms had anything to do with it.

So as an undergraduate at Allegheny College, she decided to map the prevalence of autism versus the use of certain pesticides for a project in her geographic information systems course.

“I was very interested in thinking about how things in our environment can affect our health,” she said. “I really wanted to do something that had a direct impact on people.”

That calling led her to pursue her master’s and PhD in environmental toxicology at the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS).

As Petroff graduates this spring, DEOHS is recognizing her as the 2020 Outstanding PhD Student in honor of her exceptional research, teaching and outreach to the community.

Trailing a shellfish toxin

Petroff is piecing together the neurological effects of a “tricky little toxin,” as she calls it, that threatens seafood lovers. Marine filter feeders such as shellfish, rockfish and anchovies concentrate the toxin, domoic acid, which is produced by some algae.

At high doses, it can cause amnesic shellfish poisoning, which can lead to permanent short-term memory loss.

But Petroff’s research indicates that the toxin may also harm the brain at lower concentrations.

Insights from crab-eating macaques

Her graduate work in DEOHS Professor Thomas Burbacher’s lab focuses on crab-eating macaques, primates with similar brain chemistry to humans, using relatively noninvasive techniques that have rarely been used in neurotoxicology, such as magnetic resonance imaging and electroencephalography.

She has found that macaques regularly exposed to levels of domoic acid currently considered safe for humans show changes in brain structure, which may indicate neuroinflammation.

These results could shed light on some of the behavioral changes Burbacher’s lab has seen in macaques exposed to domoic acid at these low levels, such as tremors, as well as effects on learning and memory in offspring exposed in utero.

Given the similarities between macaques and humans, “chronic exposure to this toxin may not be safe at the current regulatory limit,” she said.

Creating strong collaborations

When Petroff first visited the department, Burbacher was impressed by her knowledge, motivation and ambition—and that sense has only deepened since she joined his lab.

“Over the past six years, I have watched her grow into an exemplary, independent scientist,” Burbacher said. “She has played almost a co-investigator role.”

To fund her research, Petroff cowrote several grants with Burbacher, netting support from the National Institutes of Health, the Interdisciplinary Center for Exposures, Diseases, Genomics and Environment, part of DEOHS, and a collaborator, G. Jean Harry, who leads the neurotoxicology group at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Petroff, in turn, has been lifted up by Burbacher and others in his lab, particularly Senior Research Scientist Kimberly Grant. “Everyone I’ve worked with is so supportive—they are looking to help and want to see me succeed,” she said.

Inspiring future scientists

For several years, she and Burbacher have cotaught the introductory environmental health course for undergraduates in DEOHS. “Typically her lectures are the students’ favorites,” he said.

This quarter she is leading a graduate-level course on environmental and occupational toxicology—the first time a graduate student has taught the course.

“I’ve always been really interested in teaching, mentorship and one-on-one interaction when it comes to science,” Petroff said.

She has mentored several undergraduates during her time at UW. Since 2014, she has volunteered at the Pacific Science Center, where she designed a water-filter-building activity that captivated both kids and adults as a science communication fellow.

Last year, she and fellow DEOHS graduate students Erika Keim and Alicia Hendrix also started the Works in Progress seminar series, in which DEOHS community members present their research to one another.

The journey ahead

In her free time, Petroff loves being outside—whether on a casual hike with friends (in pre-COVID-19 times) or summiting Mount St. Helens and glissading down about 8,000 feet of elevation, as she did on a sunny day a few years ago.

Though she will miss the Pacific Northwest, Petroff will soon be starting a postdoc at the University of Michigan. She’ll study how human epigenomics relates to developmental outcomes and exposures, working with Professors Jaclyn Goodrich and Dana Dolinoy.

Eventually, she hopes to combine her love of research, teaching and mentorship into a career as a professor.

“I have no doubt that she will continue to excel at Michigan and will be a credit to our department as she continues her career,” Burbacher said.