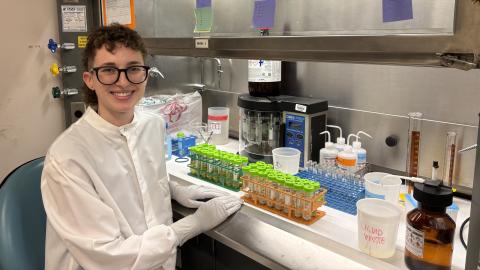

Abbie Gilbert

MS, Environmental Health Sciences

Hometown

Warrensburg, MO

Future plans

Pursuing a PhD in DEOHS focusing on infants’ exposure to heavy metals.

“I’ve had an amazing experience in my master’s, and one of the reasons I’m excited to go on with my PhD is that everyone in the department seems to be committed to offering support.”

- Abbie Gilbert

As our hair grows—starting in utero—it records exposures to potentially harmful metals and chemicals.

"You can get this timeline where you see a certain portion of the hair has higher levels of a particular metal than the rest of the strand," said Abbie Gilbert, an MS student in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS). She is one of two 2023 recipients of the Russell L. Castner Endowed Student Research Fund, which supports student research in environmental health.

Gilbert designed a study that sought to take advantage of this exposure timeline to measure participants' hair growth rates. Knowing how fast someone's hair grows could enable researchers to pinpoint more precisely when particular chemical exposures took place.

That's important because the timing of exposure to toxic chemicals, particularly in utero and in early life, dramatically affects subsequent health impacts, explained Christopher Simpson, Gilbert's adviser and DEOHS professor and assistant chair for research and faculty engagement. In contrast, blood and urine samples pick up only recent exposures.

Zapping strands of hair

Gilbert had study participants take safe levels of a zinc supplement two weeks apart, and then looked for the zinc's signature in samples of their hair.

The team expected to see two peaks in zinc concentrations in the hair corresponding with the zinc supplementations. “Those would almost act like tick marks on a ruler," Gilbert said.

If those tick marks were 5 millimeters apart in a participant's hair shaft, for example, the researchers could calculate a hair growth rate of 5 millimeters every two weeks.

To identify potential zinc peaks in participants' hairs, Gilbert traced each sample with a laser that ablated—or partially burned—the hair, including any metals incorporated into the strand while it was growing. The ablated hair material was aspirated directly into a mass spectrometer, which measured the zinc levels at each point along the hair shaft.

The Castner Award covered almost the entire cost of sample analysis, which is expensive, Gilbert said. "I’m very appreciative," she said, "and it really did make a big impact on the completion of my thesis project."

Finding more questions than answers

As often happens in science, the results of Gilbert's research didn't turn out quite as expected.

The data did not show the anticipated peaks in zinc, most likely because the amounts participants took weren't high enough to stand out from the background level of zinc people consume daily via food and water. Higher doses could have caused adverse effects, such as nausea.

Nonetheless, Gilbert said, "I really like that I get to work on something that is not fully defined and completely figured out. It means that there are a lot of questions left to be answered, which means a lot of research projects left to be done."

Applying the technology with infants in Kenya

After graduating this spring, Gilbert plans to continue studying metals in hair as a PhD student in Simpson's lab. Her doctoral research, which is part of a larger project with the UW Department of Global Health, will analyze heavy metals in the hair of newborns from Nairobi, Kenya, an area with high levels of air pollution.

"I am really interested in being able to elucidate an exposure timeline for an infant," Gilbert said, "and to overlay the neurodevelopmental timeline to see if any identified exposures also correspond with sensitive time windows for the infant."