Picture-perfect produce at your local market is the surest sign of summer in the Pacific Northwest.

Those berries, cherries and other fruits and vegetables arrive in stores Instagram-ready thanks in part to farm laborers who apply pesticides to agricultural crops throughout the year.

But that work can put farmworkers and their families at risk of pesticide-related illnesses, even when they use special clothing, masks, gloves and other personal protective equipment. Pesticide residue can be transferred to their skin, clothes, vehicles and homes.

The Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) pioneered the use of fluorescent tracer technology to test the effectiveness of protective equipment used by people who mix and apply pesticides.

It’s a technique now used to educate people around the world on the importance of safe pesticide-handling practices.

Testing protective gear

DEOHS Professor Richard Fenske developed the technique in the 1980s to test the level of protection provided by personal protective gear in the field. His team found pesticides were penetrating the equipment through openings such as at the neck.

“Pesticide handlers in our studies saw fluorescent tracer glowing on their skin and clothes and grasped immediately the extent of contamination that had occurred,” said Fenske, who is the department’s associate chair.

Training technique in use worldwide

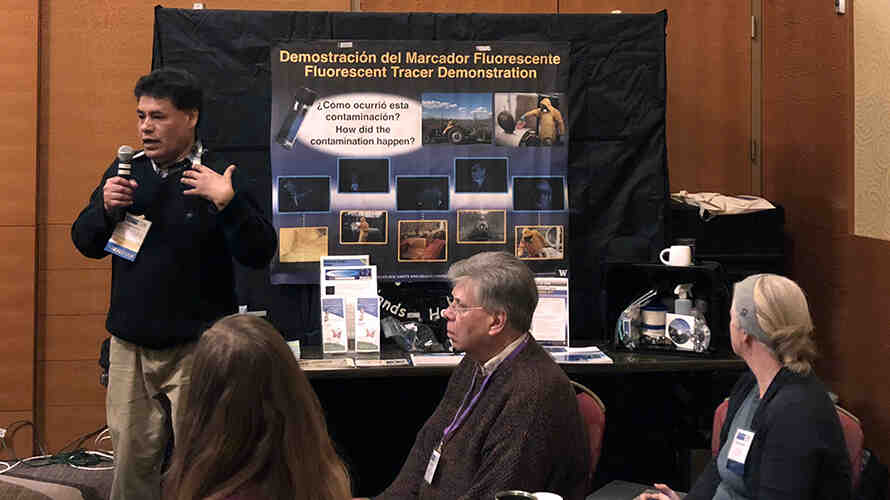

Today, we use that same technique to demonstrate the risks of pesticide contamination during trainings with farmworkers, safety managers and others across the Pacific Northwest.

We also developed a training kit and manual available in English and Spanish that is used by trainers across the United States and in Latin America, Asia and Europe.

Glowing in the dark

During trainings led by our Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center, a non-toxic substance mimicking a pesticide is sprayed on a person’s hands.

Under normal lighting, the substance is invisible. Yet it leaves behind small traces as the person touches his or her skin, clothes or other surfaces.

After a few minutes, trainers ask people to pass through a darkened booth under blacklights so they can see all the places the faux pesticide has left its mark.

“Seeing is believing in this case,” Fenske said. “The message is direct and more powerful than any lecture.”