Minola de Silva

BS, Environmental Public Health

Hometown

Seattle, WA

“It opened my eyes to environmental justice issues that rural communities can face.”

-Minola de Silva

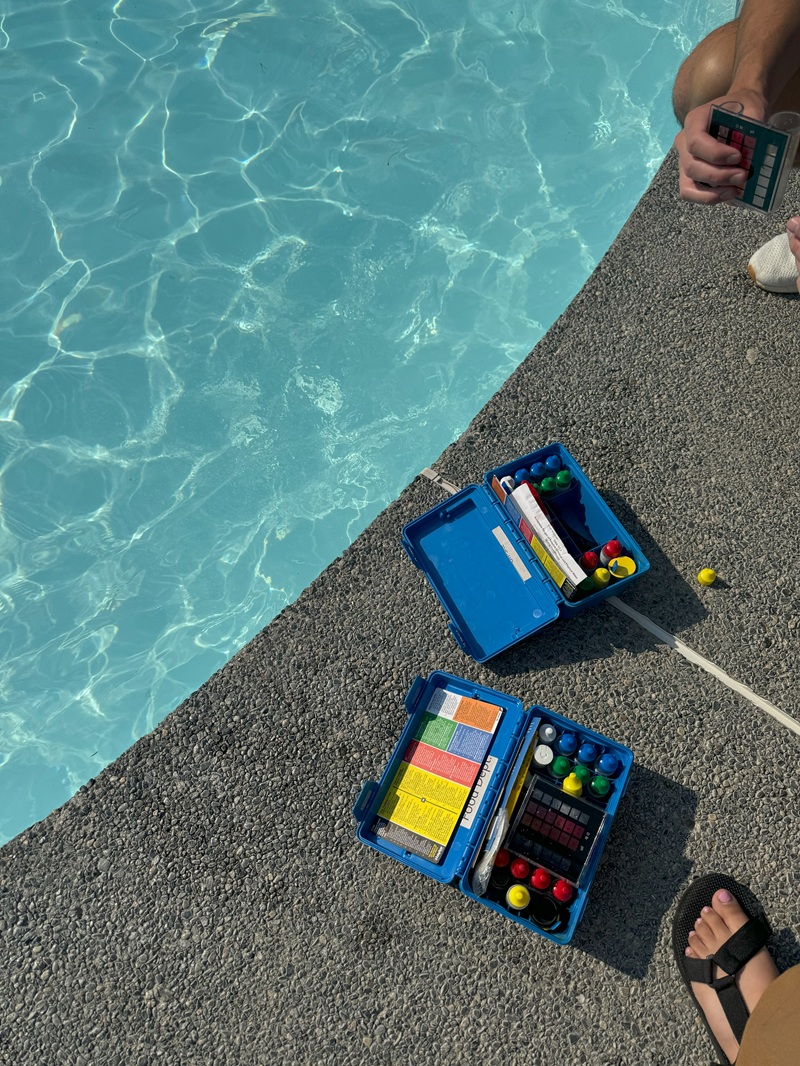

In the space of three short months, Minola de Silva got to inspect pools, investigate waste complaints, track down sources of foodborne illness, conduct an entire study on nitrate contamination in drinking water, and shut down a food vendor for safety violations.

That’s the appeal of an environmental health internship in a rural area, she said. The range of everyday opportunities is impressively wide.

De Silva, who graduated with a bachelor’s degree in environmental public health in December 2024, interned with the Chelan-Douglas Health District in North Central Washington in the summer of 2024.

Her experience was made possible by the Hatlen Scholarship, which supports UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Sciences (DEOHS) students in summer work in rural counties in Washington state.

The Jack Hatlen Scholarship Fund was established to honor Associate Professor Emeritus Jack Hatlen, who led the DEOHS undergraduate program for nearly 40 years.

“I was able to do a lot more than I expected or predicted,” she said. “Rural public health departments often experience a lot of different issues and are managed by a smaller group of people. I was able to see and do things that I probably wouldn’t have been able to see or do at a larger department.”

Nitrate toxicity study

That included a study of nitrate contamination in Group B water systems, which serve fewer than 25 people. De Silva and colleagues found that six of the 15 water samples they collected had unsafe levels of nitrates.

Elevated nitrate levels can cause significant health problems in adults and can be life-threatening for infants. When ingested, nitrates break down into nitrites, which bind to hemoglobin and reduce the bloodstream’s ability to carry oxygen, a condition known as methemoglobinemia, or “blue-baby syndrome.”

Common sources of nitrate contamination include fertilizer runoff, animal waste and landfills.

De Silva and colleagues conducted the nitrate study in Bridgeport Bar, a low-income region of Douglas County. Residents connected to unsafe water supplies were notified immediately.

“It opened my eyes to environmental justice issues that rural communities can face,” she said. “These smaller systems aren’t monitored routinely, the way large systems are. I was struck by just how dangerous that can be. With nitrate toxicity, there’s no taste, there’s no color. It’s very easy to miss."

Hands-on experience

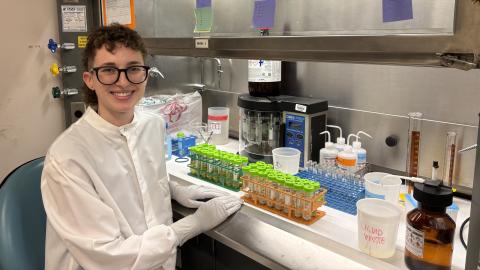

As part of the nitrate investigation, de Silva collected field samples, analyzed them in a lab, compiled the results, and presented her research at a poster session in December. “I felt like I was involved every step of the way,” she said. “It was an incredible opportunity, and it meant a lot to me.”

Teaching Professor Tania Busch Isaksen, undergraduate program coordinator for DEOHS, emphasized the importance of rural public health work and internships like de Silva’s.

“An important part of our mission in DEOHS is to prepare the future environmental public health workforce in response to employer and community needs across the state and region,” she said. “The Hatlen award allows us to ensure internship opportunities exist in our rural communities.”

Real-life lessons in communication

In her work with the Chelan-Douglas Health District, de Silva found real-world applications for the lessons she learned in her UW classes, especially around public health communication. She was careful not to create panic when telling people about a possibly dangerous situation, while still communicating how serious the problem was.

And when a routine inspection found that a vendor wasn’t maintaining safe temperatures for his food — along with other safety violations — de Silva and her colleagues had to shut him down on the spot.

“It was difficult to communicate that it wasn’t personal, that we were just trying to keep people safe,” she said. “We weren’t trying to get anyone in trouble.”

De Silva, who grew up in Seattle, was drawn to the study of infectious disease after taking biology in high school but also felt a passion to work on climate change. “When I found the environmental health major, it became the perfect opportunity to learn about both fields at the same time, especially their intersection,” she said.

After graduation, de Silva joined Professor Scott Meschke’s microbiology lab as a research scientist.