Despite efforts to stamp it out, tuberculosis (TB) is still one of most deadly infectious diseases worldwide, leading to 1.5 million deaths a year.

Part of the challenge in combating this preventable, treatable disease is that only about half to two-thirds of people with TB are diagnosed. The other third often don’t know they are sick and can spread the disease.

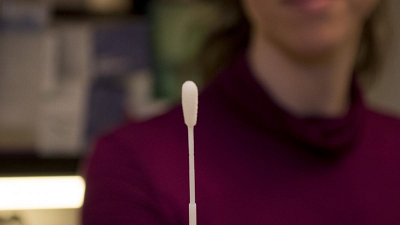

To stop the spread, DEOHS Professor Gerard Cangelosi wants to make testing for TB as easy as a home test for COVID-19. In 2015, he and colleagues developed a test that involves gently scraping the tongue with an oral swab—a quicker, easier and safer method than the standard TB test, which requires people to cough up sputum from the lungs.

The approach would allow screening for the disease in high-transmission community settings such as schools, workplaces, prisons and households. It could also make it much easier to test kids for the disease, and lower the risk of transmission to healthcare workers collecting samples.

The method is now building momentum: it’s been verified by labs around the world and met with enthusiasm in regions where the disease is endemic. Recently, Cangelosi’s lab has been taking steps to improve the method’s sensitivity and understand user preferences for it in high-transmission settings such as border crossings.

The data they are gathering will contribute to future applications for endorsement of the method by the World Health Organization.

Catching more TB cases

Cangelosi and colleagues, as well as other labs, have shown that oral swab testing detects TB in 75% to 95% of cases when compared with sputum-based methods. They have evaluated the method in partnership with dozens of labs worldwide, including the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative (SATVI) at the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

"When you detect a case, you can put that person on treatment, and they're no longer spreading it around,” Cangelosi said. “So 75% sensitivity is much better than nothing in these settings, but we'd like to get it closer to 100%.”

To do this, Cangelosi’s team is working with researchers at Northwestern University who are adapting a swab-based testing platform originally designed for COVID-19 for use with TB samples.

Improving TB diagnosis in kids

The swab method could be especially helpful for diagnosing children with TB, Cangelosi said, because they have a hard time producing sputum without the help of a nebulizer.

Children also have a lower load of the bacteria that cause TB in their lungs than adults, making it more challenging to detect the disease using sputum. Clinicians often rely on other samples, such as a gastric lavage, an invasive method that requires a hospital stay.

To test the mouth swab method in children with TB, DEOHS research scientists Rachel Wood and Alaina Olson recently worked with a lab run by Baylor College of Medicine in the Kingdom of Eswatini in Southern Africa.

Many children in the clinic also have HIV, which makes it even more difficult for them to produce a sputum sample.

“Any sensitivity we can get with the oral method is good, especially when it’s less invasive for kids,” Wood said.

The user experience with tongue swabs

Cangelosi’s team is also exploring whether healthcare workers and people being screened for TB prefer the swab method.

DEOHS PhD student Renée Codsi is leading a study on implementation of tongue swabs for TB screening with migrants. She recently interviewed migrants and healthcare workers in reception centers for migrants in Milan, Italy, to learn more about their testing preferences and the barriers to seeking and providing care.

Most people said the swab method was “so much easier and more comfortable” than the messy, hazardous process of producing a sputum sample, Codsi said.

“This is an opportunity to screen people before they become symptomatic and get them on treatment before they spread it and before it turns serious for them,” she added.

The project is a collaboration with a team led by microbiologist Dr. Daniela Cirillo of San Raffaele Scientific Institute and partners at Institute Villa Marelli and the nonprofit EMERGENCY.

Guided by community-based participatory research, Codsi worked with Copan Italia, the company that produces swabs for TB testing, to create a series of videos in 15 languages and illustrations demonstrating how to self-swab for TB screening research.

The case for swabs

In Eswatini, Wood and Olson received positive feedback from government officials and TB clinicians about the oral swab method.

It was great to hear “how excited they were to have more options, and how many more people they would be able to reach,” Wood said. “The best part of what we do is seeing how what we’ve worked on in the lab can make a difference in TB diagnosis and therefore people’s lives.”

Previously, the method’s reception has been limited by its lower sensitivity compared to sputum samples. But as Wood noted, oral swabs are not meant to replace sputum samples.

“This method can expand our reach to places where sputum samples aren’t possible: workplaces, schools, and in screening household contacts of people with TB,” she said.

Meanwhile, the method is gaining more acceptance since the COVID-19 pandemic made home testing with nasal swabs more familiar.

“We’re all so much more comfortable with swabbing ourselves now,” Wood said. “We’d love to see something similar happen for TB.”