As the world ramps up efforts to combat COVID-19, a new tool that could revolutionize detection of another deadly respiratory disease—tuberculosis (TB)—is moving closer to reality.

People can be contagious for up to 12 weeks before they develop symptoms of TB, which killed 1.5 million people worldwide in 2018.

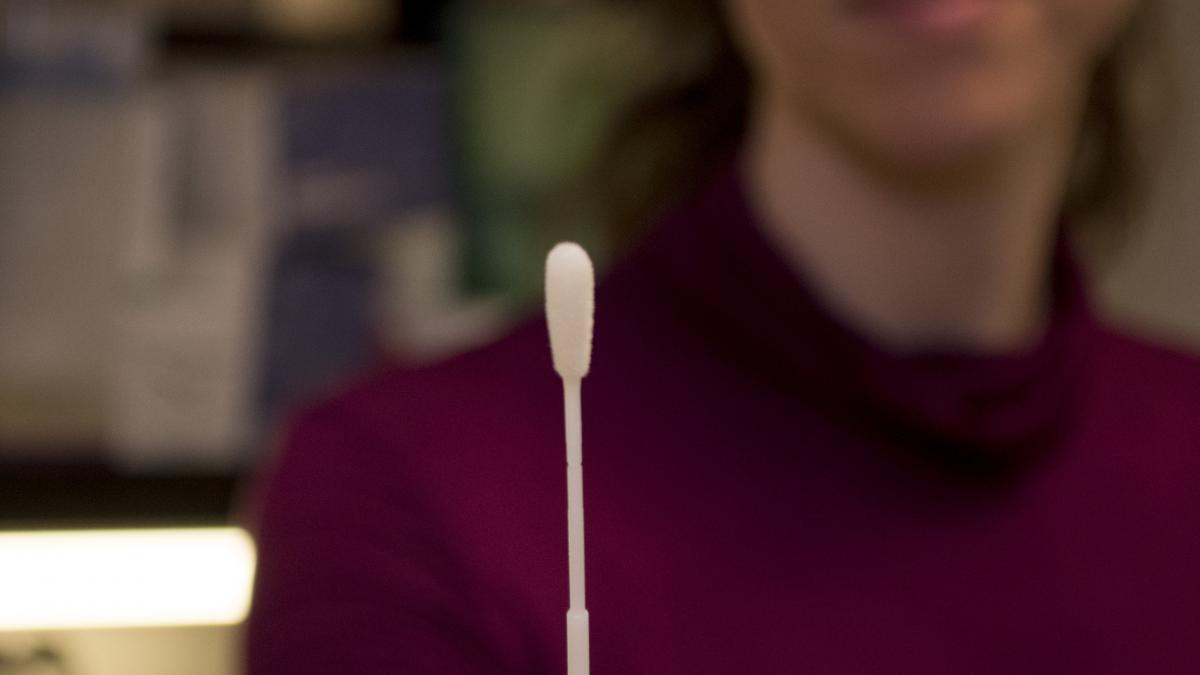

A simple mouth swab test for TB developed by Professor Gerard Cangelosi in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) and colleagues could help detect cases of the disease sooner, speeding up treatment and preventing the illness from spreading.

Cangelosi and collaborators recently received a new $1.2 million grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to improve the test’s sensitivity and develop a way to provide rapid results at the point of care. It is one of several grants Cangelosi’s team has received from the Gates Foundation to support their work.

If the team is successful, the method could be used to screen people for TB in workplaces, schools, prisons and households.

TB testing, Q-tip style

The standard way to test for TB is to collect sputum—“this gloppy stuff from the lungs,” as Cangelosi puts it.

Coughing up a sample can be difficult for patients, especially children, and potentially hazardous for health care workers. The method is not recommended for people with HIV, who made up 11% of TB cases in 2015.

In contrast, the oral test developed by Cangelosi’s team is painless and quick. It involves gently scraping the tongue with a long swab resembling a Q-tip.

“It’s by far the easiest way to collect a sample from somebody,” Cangelosi said.

The oral method detects about 90% of TB cases determined by sputum sampling, based on clinical studies.

Now the researchers are working to capture the remaining 10%.

Increasing sensitivity and speed

To make the test more sensitive, researchers plan to modify the swab design to collect more bacteria from people’s mouths.

“We think we’re only getting a small fraction of what’s available there,” Cangelosi said.

They are also developing new sample processing methods custom-designed for swabs that could provide quick results right at the testing location.

Currently, the swabs must be sent to a lab to undergo a polymerase chain reaction test for the bacterium.

Testing in Cape Town and Seattle

Adjustments to the method will be clinically tested in partnership with Dr. Angelique Luabeya of the South African Tuberculosis Vaccine Initiative (SATVI) at the University of Cape Town and her colleagues, as well as researchers at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban. SATVI has led much of the clinical testing of the method so far.

Cangelosi calls South Africa a “global epicenter” for TB research, with outstanding scientists, universities and research infrastructure in a place that also has a high incidence of the disease.

The team also hopes to test the updated method in Seattle in collaboration with the TB Control Program of Public Health–Seattle & King County. King County has about 100 cases of TB annually.

But do you like it?

-sm.png)

Do health care workers prefer the oral swab method? The team will also evaluate this question, in collaboration with DEOHS Lecturer Nicole Errett.

“My mom was a nurse, and she always told me that one of things she hated most about being a nurse was collecting sputum,” Cangelosi said.

So far, he said, health care workers have been “extremely enthusiastic” about the method, especially those who work with pediatric TB patients.

Self-testing for TB

The team will also evaluate whether at-home self-testing could work.

Self-swabbing would allow people to take multiple TB tests over time and have a greater chance of picking up an infection. The approach has become familiar to people through genetic testing companies like 23 and Me, Cangelosi said.

Eventually, Cangelosi hopes the oral method could be adopted to screen people for TB in workplaces where exposure is intensive, such as garment factories and mines.

“You can’t collect a sputum sample at work,” he said.

Other team members at the University of Washington include DEOHS Lecturer Nicole Errett; Rachel Wood, Alaina Olson and Kris Weigel, research scientists in DEOHS; Grant Whitman and Renee Codsi, master’s of public health students in DEOHS; Infectious Disease Fellow Ethan Valinetz; Department of Global Health Professor Paul Drain and Department of Bioengineering Professor Paul Yager.