As wildfires burn across the western United States—intensified by warmer, drier conditions caused by climate change—the forest workers who help prevent such fires are more critical than ever.

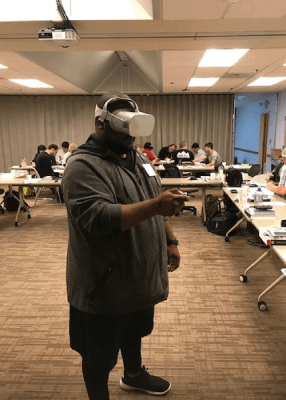

A new project led by Nancy Simcox, lecturer in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS), is using virtual reality (VR) to design a training for these workers without putting them in harm’s way. The project was funded recently by a $175,000 grant from the Washington State Department of Labor & Industries.

“VR is the training for the 21st century—producing simulations that can create life-saving situations,” said Simcox. She is collaborating with Brian Cleveley, senior lecturer of virtual technology and design at the University of Idaho, to create a virtual world that will engage these workers, many of whom are from Latinx communities, in safety and situational awareness training in English and Spanish.

The training will digitally simulate scenarios workers could experience in the field. Using a headset and controllers, trainees will see and hear what they would in real life, from the tall Douglas firs typical of Pacific Northwest forests to the growl of chainsaws. They will be able to walk around the virtual world, assessing their surroundings for potential hazards such as thick layers of pine needles on the forest floor. They will also interact with simulated machines and other trainees, and make decisions that lead to certain outcomes.

When a tree is falling

Forest workers who help reduce fuel loads and lower the risk of wildfires face many hazards on the job. They work in rough and sometimes unpredictable terrain, encounter burning and falling trees, operate dangerous equipment and can experience ergonomic risks associated with heavy lifting.

“It’s loud and noisy, so being able to communicate as a team when you’re out in the forest is important, as is making sure everyone knows where everyone is when a tree is falling,” Cleveley said.

VR enhances learning by harnessing the experience of making mistakes in a controlled environment.

“When I started to hear about VR, it seemed like a no-brainer,” Simcox said. “We could put people in an environment where they can take actions and make decisions, and they won’t get hurt.”

As director of Continuing Education Programs and Outreach in DEOHS, Simcox has extensive experience in environmental and occupational health training for practicing professionals in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Alaska.

“The value of the virtual world is that you can make right and wrong decisions, and even if you make a mistake and there were a bad outcome, you’re still there to try it again,” said Cleveley. “We have a saying: ‘Real-world outcomes without real-world consequences.’”

Creating a digital forest

To ensure the VR training reflects the real world as much as possible, the team invited forest workers and their employers and trainers to sit down with Cleveley’s “virtual world builders.” These partners have helped designers render the forest work environment—from what people are wearing to how they’re holding chainsaws. They have also suggested critical safety topics that trainees may struggle to grasp with current educational tools.

The team hopes to make language less of a barrier to training by offering the simulation in both English and Spanish.

The UW team is partnering with Washington State University’s extension program, which offers forestry education, to pilot the VR training in their classrooms. WSU experts are also providing guidance on simulation design.

The structure of the training is based on research conducted by DEOHS’s Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health (PNASH) Center, which developed resources highlighting the hazards of forestry work.

Simcox and Cleveley also plan to expand the training to include an augmented reality module for smartphones and tablets to allow employers and supervisors to supplement safety talks and reminders in the field.

This post was adapted from the original story, available here.