Graeme Carvlin

PhD, Environmental and Occupational Hygiene

Hometown

Flemington, NJ

Future plans

Continuing his work as an air monitoring specialist with the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency.

“If we can make air-quality monitors more accessible, communities and individuals can get timely data to help address air pollution in their own neighborhoods.”

- Graeme Carvlin

Where would a chemist with a serious electronics hobby and an interest in programming and atmospheric science go if he wanted to combine it all into one career focused on public health?

For Graeme Carvlin, it all came together in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS), which recently named Carvlin as our 2018 Outstanding PhD Student.

Carvlin’s research led to the development of an innovative technology that empowers local communities with up-to-the-minute data about air quality at a price that is about 95 percent less than the cost of existing sensors.

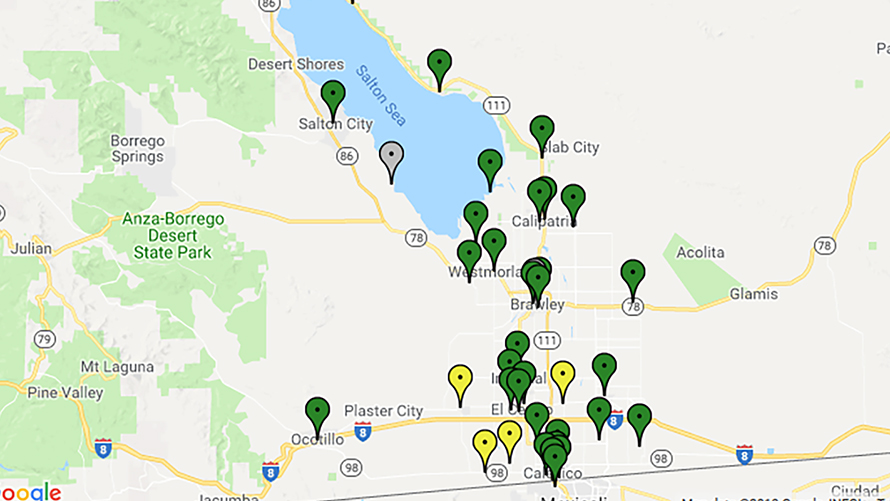

The monitors provide real-time air-quality data at the neighborhood level for several DEOHS-led research studies, including one investigating the role of air pollution in communities along the California-Mexico border with some of California’s worst hospitalization rates for childhood asthma.

DEOHS Associate Professor Edmund Seto, who leads that project, said Carvlin’s work played an important role in 2017 California legislation that uses revenue from the state’s cap-and-trade program to fund air monitoring in communities statewide.

Lower cost, better data

Carvlin, who graduates this summer, worked with Imperial County, CA, to build and install a system of 40 air monitors to gather real-time data about local air pollution.

The technology he developed is also being used in Seattle as part of a study investigating the link between air pollution and dementia and as part of a nationwide study examining the connection between air pollution and cardiovascular disease.

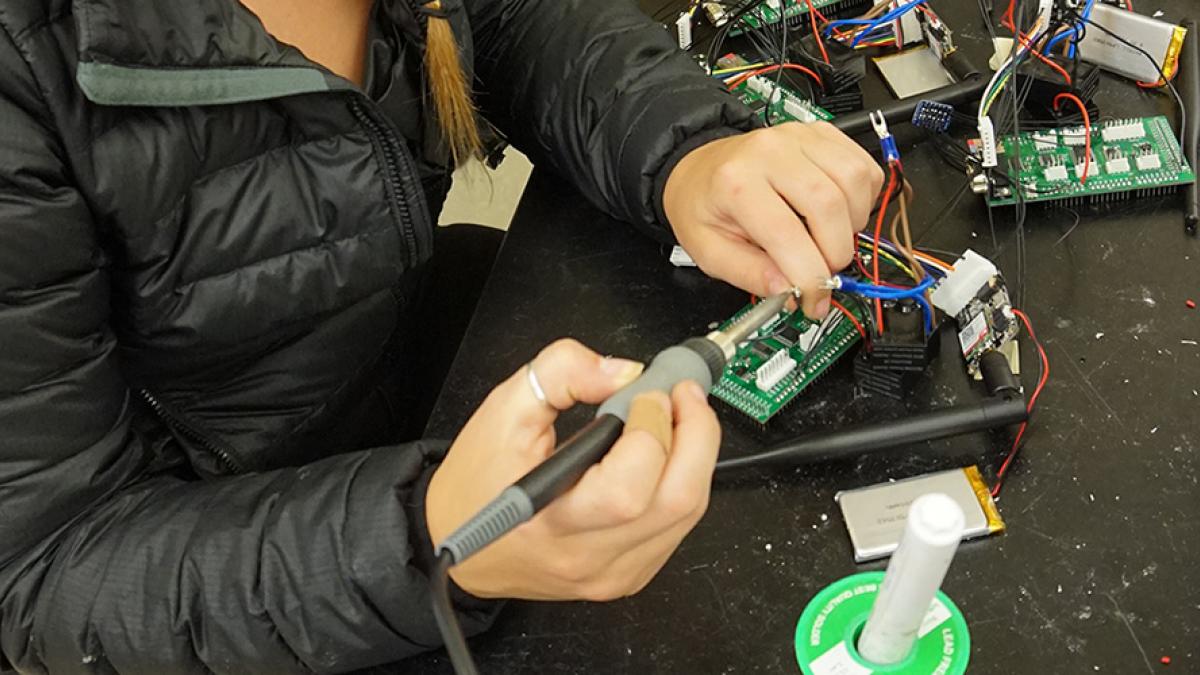

The lunchbox-sized monitor includes a particle counter, gas sensors that measure gases regulated by the US Environmental Protection Agency, a microcontroller and networking card. Unlike traditional sensors that measure air pulled through a filter, the monitor actively samples air passing over its sensors, transmitting the data to a UW database.

Traditional air monitors cost about $25,000 each, he said. Carvlin’s version currently costs about $1,500.

Carvlin and a team of student researchers working with Seto rigorously tested and validated the new technology. Some monitors were installed next to government-tested regulatory monitors so they could compare readings.

And that comparison led to an unexpected finding: The upper limit of the government monitors was set too low to catch spikes in air pollution. They weren’t able to capture data that showed days when the air quality dropped. The government ultimately adjusted its own air monitors based on Carvlin’s research.

Empowering communities

Carvlin arrived at the UW in 2014 with a master’s in chemistry from the University of California, San Diego, and learned about DEOHS and Seto’s research through a colleague.

“I felt it was a good set-up there to pursue what I was interested in,” he said. “I had a lot of leeway to work on the technical side of things while also pursuing my interest in improving public health.”

Pollution is linked to one in every six deaths worldwide, with two-thirds of those deaths attributed to air pollution. High-quality, affordable air monitors will enable more communities and government agencies to collect data and work to reduce air pollution emissions, Carvlin predicted.

That’s already happening in Imperial County, where local community members were handed control over the monitoring system and are now talking with regulatory authorities about ways to improve air quality.

What’s next: personal air monitors

Soon, the monitors will be commercially available. In 2017, Seto and Carvlin received a grant to refine the monitor’s design from the CoMotion Innovation Fund, a partnership between UW CoMotion and the Washington Research Foundation that supports promising innovations.

Now they are finalizing the technology for manufacture by further reducing the cost and assembly time.

Carvlin is also working on a smaller personal version—wearable technology the size of a cell phone that will offer additional features, such as GPS and an accelerometer, and let consumers monitor ambient air quality in real time.