Could living next to a busy freeway make you more likely to develop dementia?

Air pollution, which contributes to respiratory and heart disease, may also trigger cognitive decline and dementia as people age. But many questions remain about this association, including exactly how air pollutants damage the brain, and whether noise and other environmental factors also contribute to these harmful effects.

Now Dr. Joel Kaufman, professor in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS), is using a high-resolution model of air pollution to tackle these questions in collaboration with researchers at UW and Boston University.

The team, led by Jennifer Weuve, associate professor of epidemiology at Boston University, recently received two grants from the National Institute on Aging to delve into epidemiological data from several large, diverse cohorts of older adults in the US. The team also includes Adam Szpiro, associate professor of biostatistics at UW, and Michael Young, senior postdoctoral fellow in DEOHS.

If the team finds that air pollution, noise, or both strongly contribute to dementia, there may be some reason for hope. Since both factors can be controlled, Kaufman said, dialing them down may be an effective way to reduce the rate of dementia.

Addressing air pollution

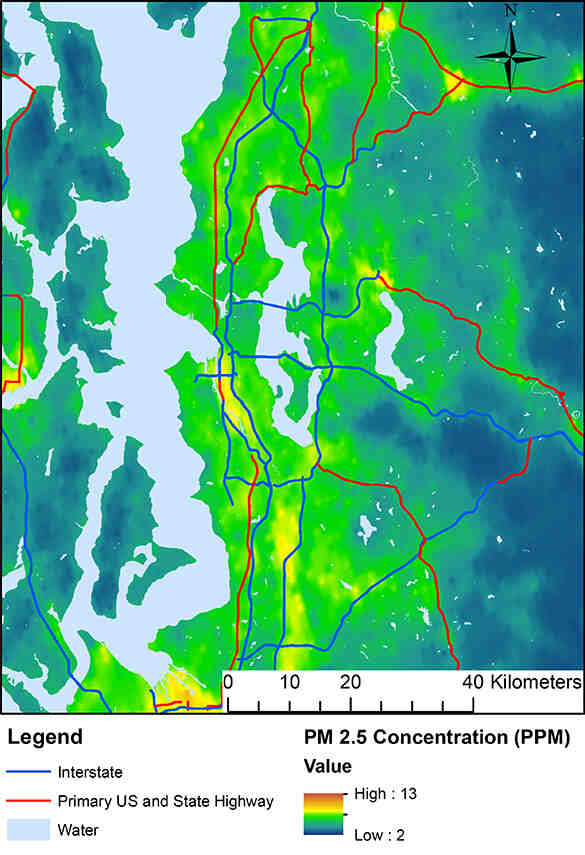

Plug an address into the system developed by Kaufman’s group and collaborators, and you can find out roughly how much air pollution someone living there is exposed to, and how those levels have changed over time.

To make these estimates of pollution levels, the model takes into account hundreds of geographic variables including the distance from known sources of air pollution and major roadways, traffic levels on those roads and the amount of nearby green space.

Using the model, Kaufman’s team will estimate air pollution over time at the addresses of participants in several long-term studies of cognition and aging, including the Religious Orders Study and Memory and Aging Project (ROSMAP) study, and examine whether participants who developed dementia had more exposure to pollution than those who didn’t.

Kaufman’s team and several other UW faculty developed the statistical model in the 2000s as part of the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and Air Pollution (MESA) Air Study, a decade-long effort which established that long-term exposure to air pollution contributes to heart disease. The team's models have continued to improve and are now validated across the continental United States.

“In the past, people assumed that air pollution was primarily a hazard to the lungs because you breathe it in,” Kaufman said. “We moved from an understanding that air pollution causes respiratory problems to realizing it also causes cardiovascular problems. And then it made sense to ask: what else could it be causing?”

Particles in the brain?

Scientists don’t know how air pollution might cause dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, something the team is investigating.

“One of the questions we have is whether these air pollutants can actually get directly into the brain,” Kaufman said.

Studies in rats show that the smallest particles can be taken up into the brain directly through the nose—via a set of nerves that processes smell. This could explain why the loss of sense of smell is often an early sign of dementia in people, Kaufman said.

The team will look for particles in the brain tissue of deceased participants in the ROSMAP study, who agreed to donate their brains for analysis after death.

They will also examine these brains for evidence of Alzheimer’s disease and its potential connection with air pollution. Kaufman’s team has already been exploring this link through work on the Ginkgo Evaluation Memory study, and DEOHS Professor Lianne Sheppard is tackling similar questions.

Sound and sense

Exposure to noise increases stress and blood pressure, which can cause strokes and lead to dementia. But since areas with polluted air are also often noisy, it’s a challenge to separate the influence of the two factors.

In another project, the UW-Boston University team is examining whether noise plays a role in cognitive decline, and how it might interact with air pollution to affect the brain.

The researchers are developing models of noise analogous to Kaufman’s air pollution model, although there is not as much available data yet for noise exposures in the US as for air pollution.