A simple, inexpensive method to capture the new coronavirus in wastewater could speed up detection of COVID-19 outbreaks in nursing homes, dorms and low-resource settings, according to new research by UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) Professor and Associate Chair Scott Meschke and colleagues.

The secret? Just add milk.

Skimmed-milk flocculation, an established method for removing virus from wastewater, performed the most reliably among five methods the team tested in a study recently published in Science of the Total Environment.

“I think there’s great potential for this as an early-warning system, and for detecting new cases of COVID-19 circulating after it’s been cleared from a community,” Meschke said.

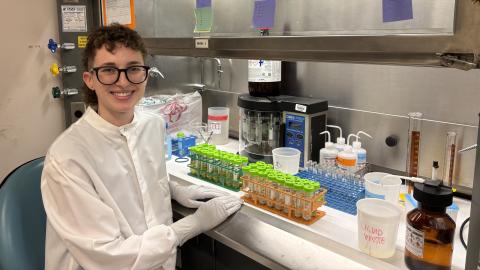

"It’s also really easy, so we hope that there aren’t a lot of barriers for people to be able to do this method," DEOHS PhD student Sarah Philo, the first author of the study, recently told Q13 Fox.

Video: Simone Del Rosario/Q13 News.

Adapting environmental surveillance for COVID-19

Meschke’s team is adept at hunting down sources of infection in wastewater, a field known as environmental surveillance.

Their simple field filtration method for capturing poliovirus from water has been used in Pakistan and other countries where the virus is endemic as an early-warning system for outbreaks.

When COVID-19 first hit the US last winter, Meschke and his team began investigating how to adapt their technique for coronavirus, with funding from the UW Population Health Initiative. Like poliovirus, SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus causing the COVID-19 pandemic, is expelled in the solid waste of people infected with the virus.

They tested their filtration method along with approaches used by other research groups to look for the coronavirus in sewage, including ultrafiltration and precipitation with the polymer polyethylene glycol.

The method that worked best is a single step of the protocol they used to capture poliovirus: instead of filtering the sample first, they add skim milk directly to raw wastewater.

Next, they add acid and shake the sample to create tiny milk curds. The virus sticks to the curds, which are collected by centrifugation, allowing the team to isolate and detect the viral RNA.

COVID-19 in Seattle’s sewers

The team tested the methods on samples from the intake of three wastewater treatment plants in Seattle last spring and summer. Using the skim-milk method, they found COVID-19 in nearly half of the samples.

Intriguingly, the researchers found a presumptive positive result for novel coronavirus in a wastewater sample taken last February in Seattle for another study, before community transmission of COVID-19 was detected in Washington state.

Although the recent high incidence of COVID-19 in Seattle helped the team evaluate the different methods, Meschke said this environmental surveillance approach would be most effective for detecting new outbreaks of the virus in places where it has been brought under control or hasn’t yet taken hold.

“Just because we can find it in sewage doesn’t mean we should—we need to know that we can use the result to benefit public health or make a decision,” he said.

Preventing communal spread

The method could be particularly valuable for monitoring communal living settings, such as nursing homes or dorms.

If you get a positive result in these settings, Meschke said, “you can tell that it’s only coming from that population, so you could screen them to make sure it can be contained.”

Researchers using a similar wastewater monitoring approach at the University of Arizona interrupted an outbreak in a dorm earlier this year.

In an effort to zero in on these kinds of settings, Meschke’s team is also working with Mari Winkler, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, who is sampling pump stations and manholes in Seattle representing neighborhoods such as UW’s Greek Row.

From Washington to Bangladesh

As Meschke’s team continues to monitor Seattle sewage and optimize the method, they are also working with the Washington State Department of Health to explore how to apply environmental surveillance methods across the state.

“Getting into smaller communities could have a lot of benefit,” he said, because monitoring could be set up at localized facilities or isolated regions of a larger distribution system.

The simplicity of the skim-milk method could also be particularly useful in low-resource settings. Meschke’s team is collaborating with Seattle nonprofit PATH to lead a technical assistance committee for several international projects to detect COVID-19 in environments without traditional sewers, including in Bangladesh, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Malawi, Myanmar and Nepal.

Other DEOHS coauthors of the study are Erika K. Keim, Rachael Swanstrom, Angelo Q.W. Ong, Elisabeth A. Burnor, Alexandra L. Kossik, Joanna C. Harrison, Bethel A. Demeke, Nicolette A. Zhou, Nicola K. Beck and Jeffry H. Shirai. The project was funded by the UW Population Health Initiative.