Aesha Mokashi

MS, Environmental Health Sciences

Hometown

Portland, OR

Future plans

Working as an environmental health scientist with King County and internationally.

“Coming to this program, where people are actively working to fix these (urgent public health) issues, makes everything feel a little bit better.”

- Aesha Mokashi

Several years ago, healthcare workers in King County were concerned to find that children in the county’s Afghan immigrant community had much higher levels of lead in their blood, on average, than kids in other local immigrant communities.

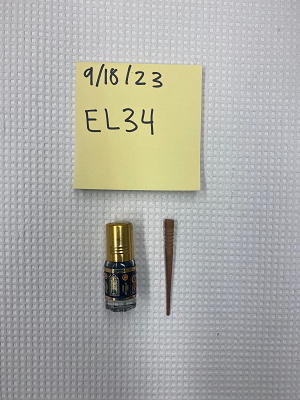

Through home investigations, researchers linked the finding to the use of traditional eyeliners known as kajal, kohl or surma. Some contain up to 84% lead, the Hazardous Waste Management Program in King County (Haz Waste Program) found. The neurotoxic metal is naturally present in materials used to make the products, particularly the mineral galena, or lead sulfide.

In the Afghan community, these eyeliners have aesthetic, medicinal and religious significance and can be applied to both children and adults.

“Little kids tend to rub their eyes. If these eyeliners have lead in them, and kids are ingesting the lead, then that can get into the bloodstream,” said Aesha Mokashi, an MS student in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) who is researching the issue through an internship with the Haz Waste program.

Community-based solutions

In response to the findings, the Afghan Health Initiative partnered with the Haz Waste Program to research solutions. They asked the agency to test lead levels in a range of potentially safer eyeliners, such as those available at local pharmacies, in addition to imported samples.

The import of traditional eyeliners is technically banned by the US government, but the products can be easily obtained online via merchants like Amazon and Etsy.

For Mokashi, the project was a perfect blend of her interests in children’s environmental health, traditional cosmetics and community-engaged research.

“One thing I really liked about this project is that it's really been influenced by the community. It isn't just us coming in and saying, there's a problem, and we're going to fix it,” she said.

“It's been really informational for me too, because in my Indian culture, we use these traditional cosmetics a lot. I’m learning about what I use on my body and how it could be impacting my health.”

Screening home products for lead

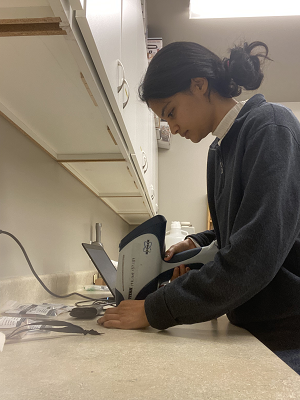

During her internship, Mokashi has been working in the King County lab to analyze lead in both imported eyeliners and those obtained at local pharmacies.

So far, the team has found that imported samples have up to 720,000 parts per million (ppm) of lead, in comparison to the US limit of 10 ppm for cosmetics.

The team’s recent data on samples from local pharmacies show that though nearly all brands had lead levels below 10 ppm, all except one sample exceeded the Washington state limit of 1 ppm.

Mokashi has also worked at events co-led by community-based organizations and King County, where community members can bring home goods—such as cosmetics, cookware and children’s toys—for immediate lead screening.

Using a handheld X-ray fluorescence analyzer, Mokashi and Haz Waste Program scientists including her supervisor, DEOHS Affiliate Associate Professor Stephen Whittaker, and DEOHS alum Katie Fellows can immediately tell participants whether something they have brought in contains significant levels of lead. If it does, the team can test the item more accurately in the lab.

The Haz Waste Program team and DEOHS researchers recently reported significant levels of lead in imported cookware.

Understanding the bigger picture

This month, the Haz Waste Program and the Afghan Health Initiative are hosting a forum for Afghan community members to share their thoughts about using lower-lead replacements for traditional eyeliner.

“It seems like such a small and easy fix, but then you actually meet with people and they might be more hesitant about it,” Mokashi said.

In addition to the challenges of conveying the health risks and building trust with communities, it’s also sometimes difficult to clearly identify safer eyeliner alternatives.

For example, some traditional eyeliners made from a mixture of burnt plant material and oil tend to have substantially lower levels of lead than those made by grinding up galena, Mokashi said. But some communities use the same name for these different products, making them hard to distinguish.

Actively making a difference

In college, Mokashi majored in biology and researched heavy metals in freshwater bodies that were linked with a childhood cancer cluster in Ohio.

The experience sparked her interest in environmental health, which deepened as she was applying to graduate school in the midst of the pandemic. Environmental public health felt to her like an antidote to the world’s most urgent problems, from infectious diseases to climate change.

“Coming to this program, where people are actively working to fix these issues, makes everything feel a little bit better,” she said. “All the people I've met have been so interesting and have such diverse backgrounds. And they're also so passionate about environmental health.”

Mokashi’s adviser, DEOHS Assistant Professor Diana Ceballos, has been a powerful advocate for Mokashi’s work and offered her a perfect balance of guidance and independence, she said.

“She looks out for me and wants the best for me,” she said. “To have someone who's so experienced in the field telling me my work is important—having that reassurance is really nice.”

Pursuing happy endings

After graduation, Mokashi hopes to continue working with the Hazardous Waste Management Program. Eventually, she would also like to apply her environmental health expertise in India to help communities there reduce lead in products like eyeliner, spices, medicines and cookware.

“I like that there's a story that you can tell with public health,” she said. “It’s often a sad story, but then, hopefully, there’s a happy ending where people have figured out: There's an issue here, and we know where it's coming from so now we can stop it.”