As wildfires spread across the Pacific Northwest last summer, the Seattle area briefly earned the dubious honor of being one of the most polluted cities on earth.

For four days, the smoky air grew so polluted that it was considered “unhealthy for all.” One news report noted that breathing Seattle air was like smoking seven cigarettes.

Climate researchers say we can expect to see longer and more severe smoke events over the coming decades with significant public health impacts. That has sparked new interest in the idea of clean air shelters that can provide respite to people affected by wildfire smoke.

Now researchers at the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) are collaborating with the Tulalip Tribes on research that could help identify the best location for such shelters on their reservation, located north of Seattle.

What are you breathing?

Wildfire smoke contains particles of less than 2.5 microns in diameter known as PM2.5—particles that are 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair. This kind of air pollution is linked to everything from preterm births to heart disease and premature death.

Experts have long been stymied on how to measure air pollution exposure at the individual level, which can vary widely depending on factors like where you live and how much time you spend outside.

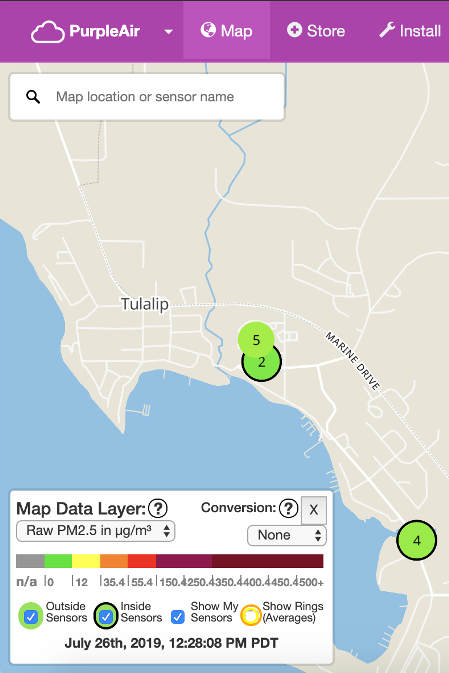

Orly Stampfer, a DEOHS PhD student in Environmental and Occupational Hygiene, is testing the use of low-cost air monitors that can measure particle levels in the air and display the data in real-time on a map.

Testing the air where children play

At the invitation of Dean Henry, a Tulalip tribal member and clean air advocate, Stampfer worked with tribal staff to deploy the sensors around the Tulalip Reservation.

She placed the monitors inside and outside a teen community center and an early learning center, as well as another outdoor location to determine how indoor air quality differs from outside, both during wildfires and during ambient conditions.

Even in the absence of wildfires, Gillian Mittelstaedt, Stampfer’s collaborator and director of the Tribal Healthy Homes Network, said people living on the Tulalip Reservation often suffer from wood smoke trapped in temperature inversions.

“These contaminants are a new and growing risk factor for those with asthma, as well as those with lung and cardiovascular diseases,” Mittelstaedt said. “Wildfires have now created a sense of crisis that has increased interest in air quality.”

The best place for clean air

The data that Mittelstaedt and Stampfer collect this year will be used to help identify the best places for clean air shelters on the reservation.

Promoting the use of clean air shelters during wildfires should, in turn, help reduce unplanned doctor visits and trips to the emergency room, Mittelstaedt said.

Shelters typically are either built or retrofitted with high-tech filtration systems and seals that help reduce fine particles, providing a safer place for people to spend time during wildfires.

In June, the city of Seattle announced a pilot program that will retrofit five public facilities, including the Rainier Beach Community Center and two buildings at Seattle Center, to serve as air shelters as early as this summer.

Do air shelters protect health?

This kind of retrofitting can be expensive. DEOHS Associate Professor Edmund Seto said research on whether clean air shelters actually reduce harm is still inconclusive.

“We know that air pollution is not healthy and that it has a broad range of health effects. We know that you should do the best you can to avoid exposure. But the solutions we have aren’t terrific,” Seto said.

"If clean air shelters are part of our strategy to protect people's health during smoke events, it is critical that we begin to evaluate their effectiveness and who may benefit from them," he said.

Stampfer recently did a literature review on the efficacy of air shelters and found little evidence to date.

“That doesn’t mean staying inside your home or an air shelter isn’t helpful,” she added. “It just means there haven’t been enough published studies on their effectiveness.”

Mittelstaedt noted that while wildfires used to be considered an acute exposure, they are now so extended and frequent that epidemiologists are beginning to consider smoke as a chronic exposure—making research like Stampfer’s more important than ever.