Can you reuse nonsurgical N95 respirators and KN95 and KF94 masks?

Yes! Tips from DEOHS Assistant Professor Marissa Baker:

These masks can be reworn until the mask is dirty, torn or wet through the mask, or the straps are stretched out or damaged.

They will last longer if you rotate your masks by resting them for at least a day between uses. Some experts suggest resting them in a paper bag for several days to inactivate any virus.

“Even during a surge, most people’s exposure to virus in the community and in most [non-healthcare] workplaces is pretty low,” Baker notes. “So honestly, the respirator will likely physically be damaged before it needs to be replaced from an exposure standpoint.”

Tips for mask fit and use:

- Improve the fit of an N95 or KN95 by pinching the metal nose clip around the bridge of the nose. This video can help you get a good fit.

- All N95s have straps that go around the back of your head. For optimum fit, one should be above your ears and the other below your ears (around your neck).

- If you have facial hair, you will get a better fit if you are clean shaven.

- Do not attempt to clean or disinfect an N95 or KN95. If you have, it is no longer effective and should be thrown out.

- There is not a shortage of N95 and KN95s.

- Find well vetted N95 and KN95 masks at Project N95.

Updated 1/28/22

How many times can a health care worker safely reuse a face mask? It’s a critical question as N95 respirators remain in short supply, forcing many health care centers around the US to disinfect and reuse them.

One of the first studies to tackle this problem with human volunteers is underway in the UW School of Medicine and the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS).

For DEOHS graduate students Renée Codsi and Grant Whitman, the study is part of their practicum research—a chance to work on an environmental health project with real-world impact.

“Everything I have been working on to date has been in the lab—and there's certainly relevance outside of the lab,” said Whitman, an MPH candidate in Environmental and Occupational Health. “But this is my first time applying that science to something more immediate.”

How do masks stand up to repeated cleaning?

The UW Medical Center and hundreds of other health care facilities across the country are disinfecting N95 masks with vapor-phase hydrogen peroxide using a system developed by research and development nonprofit Battelle.

This spring, the US Food and Drug Administration authorized emergency use of Battelle’s Critical Care Decontamination System (CCDS).

Battelle’s initial tests, using mannequins, indicated that the masks could be disinfected and reused up to 20 times. But in humans, the masks may hold up for far fewer reuses, in part because cleaning can disrupt the fit of the mask.

A recent National Institutes of Health-directed study with human subjects found that masks may fail after only three cycles of vapor-phase hydrogen peroxide treatment. However, the study did not use the CCDS.

To get a clearer sense of the CCDS’s performance, Dr. Paul Pottinger, professor in the Department of Medicine, and Staci Kvak, a hospital epidemiologist in infection prevention at UW Medical Center and a DEOHS alumna, launched the new study.

“Grant and Renée have been so helpful on this project," Pottinger said. "We are really excited to work with them and appreciate their energy and insightfulness.”

Getting the right fit

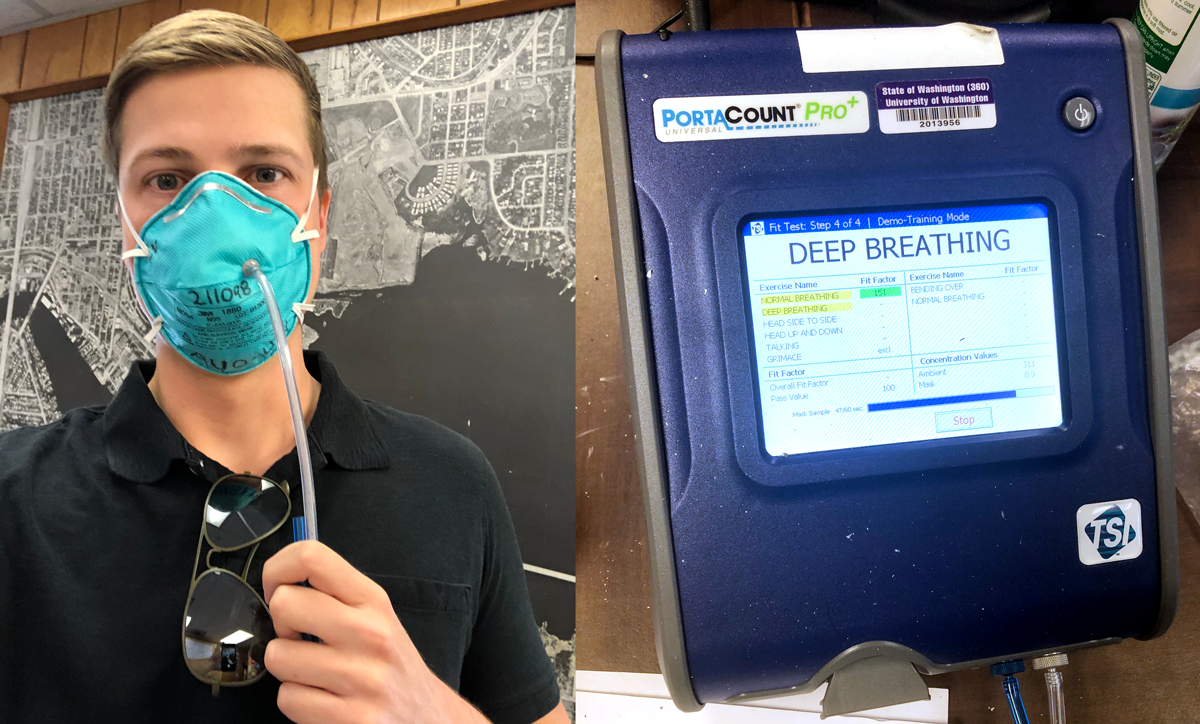

This summer, 24 faculty and staff members in DEOHS, UW Medicine and UW Environmental Health & Safety (EH&S) volunteered for the study. Whitman is one of them. To minimize risk, volunteers do not wear the masks in clinical settings.

The volunteers wear their masks for 30 minutes before they are collected at the study site and shipped to a CCDS in Tacoma for cleaning.

When the masks come back, participants do a “fit test” of each mask’s ability to filter particulates using a system that counts particles inside and outside the mask. The team is measuring how many times a mask can be reused safely if it is returned to the same user after cleaning, as well as how many times it can be reused by a different user once it has been decontaminated. The study tests up to six decontamination cycles for each mask.

Could reusing your own mask help?

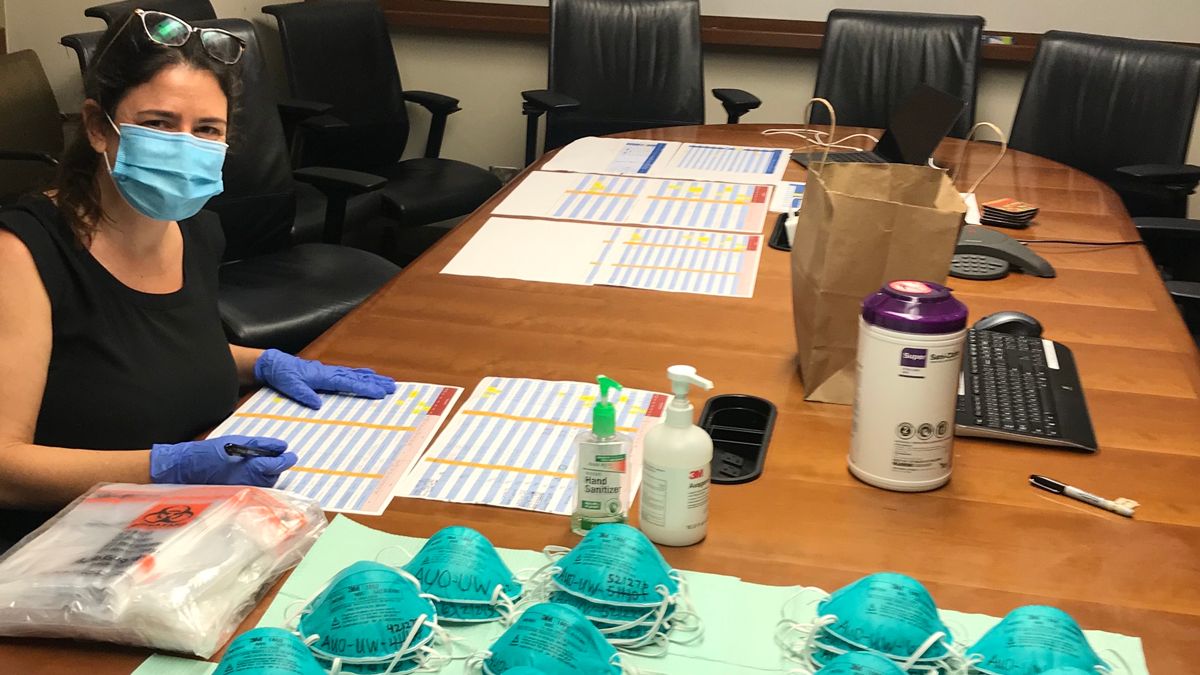

Codsi, an MPH student in One Health, is the communications and data collection coordinator for the study.

“I am interested in seeing how we can apply our study results to create a methodology for scaling this study into practice at UW Medical Center and beyond,” she said.

Researchers will have full results by the end of the summer. But Whitman has some hunches. Although he hopes the masks will hold up for six cleanings, “I am a little skeptical that they will be efficient up to that many cycles,” he said.

He also expects that masks returned to the same user will fit better than those allocated to others.

“After those masks have returned, there have been differences in the shape of the mask. Some of them are more flattened, or the nose bridge is slightly more clamped than I would have it,” he said. “It certainly seems that having your own mask could make a difference.”

Seeing the impact

Both Codsi and Whitman are working on their master’s theses in DEOHS Professor Gerard Cangelosi’s lab, which focuses on developing diagnostic tests for tuberculosis.

Whitman was drawn to infectious disease research as an undergraduate, when he was a student research assistant at the UW Center for Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases.

Codsi became intrigued by emerging diseases while doing environmental conservation and participatory action research globally. She came to UW to investigate the connections among the health of humans, animals and the environment we share. Writing a supplement for the project's institutional review board proposal was a great warm-up for writing her thesis proposal, she said.

In addition to working on data collection and analysis, Whitman has helped write a grant proposal and institutional review board proposal and made a REDCap site—used to create databases for clinical research—for the first time.

With about a year left in his program, this first taste of translational research—particularly on a project with such relevance—has made him excited to do more of it.

“I really enjoy applying science and seeing that impact firsthand,” he said.

Other study participants include Doug Gallucci, assistant director of UW EH&S, site study coordinator and certified fit testing professional; Dr. Seth Judson, UW internal medicine resident and co-investigator; Staci Kvak, hospital epidemiologist, infection prevention and site study co-investigator; Kathy Strand, UWMC employee health and certified fit testing professional; Eleanor Wade, occupational health and safety manager, UW EH&S, and study design coordinator; Dr. Seth Cohen, director of infection prevention at UWMC; Kristine Joy Culala, study organizer; Retha Hay, UWMC employee health; Adrienne Schippers, manager of UWMC infection prevention; Timothy Taylor, study organizer; and Dr. Robert Yates, Department of Surgery.