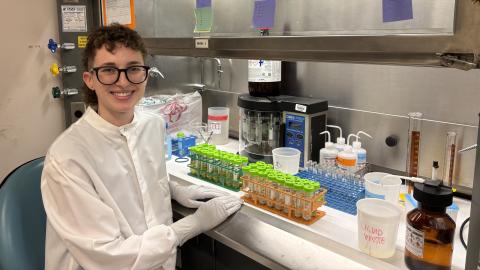

Evan Gallagher

Professor, UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences

Proudest achievements:

Showing how biochemical pathways in fish make them susceptible to toxic chemicals, and what this means for human disease; Directing the UW Superfund Research Program; Mentoring students and postdocs.

Joined DEOHS faculty:

2004

"One of the best things about academia is being able to see a deserving undergraduate, graduate student or postdoc launch onto a new job or educational experience, and ultimately a better life.”

- Evan Gallagher

Evan Gallagher, who recently retired after 19 years as a professor in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS), almost didn’t become a scientist.

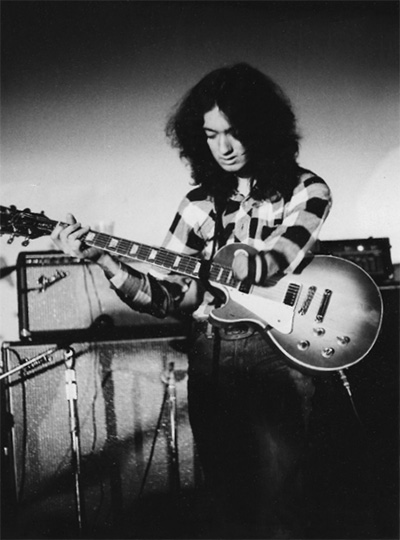

Music was his first love. At age 13, he started playing guitar, inspired by watching the Beatles on TV and thinking to himself, “I can figure that out.”

He became a musician, playing guitar in several funk and rock and roll bands. But he was also fascinated by biology, and he decided to major in it in college.

“I’ve always had an interest in nature, and how human disturbances affect wildlife as well as water quality and fish,” Gallagher said.

After graduating, his work as a field biologist at Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge in Virginia sealed his interest in environmental science, despite the challenge of long days banding ducks in freezing weather.

In graduate school at Duke University in the 1980s, he took a course in ecotoxicology, which blends ecology with environmental chemistry, physiology, biochemistry and molecular biology.

“That really spoke to me,” he said—and it set the direction of his 39-year career.

“What’s intriguing about environmental toxicology is that it’s interdisciplinary, and it involves all aspects of the ecosystem,” allowing scientists to home in on questions both large and small, he explained.

During his career at the UW, Gallagher has investigated questions such as how biochemical mechanisms make one species of fish resistant to a toxic exposure and another sensitive to it—and the implications for differences among humans susceptibility to pollutants.

As director of the UW Superfund Research Program since 2013, he and collaborators have shown how pollutants in the environment, particularly metals, harm the nervous systems of humans, salmon and other wildlife, and can even interfere with salmon’s sense of smell.

“Evan’s work on the pathways of olfaction have made many important contributions to understanding human impacts in environmental toxicology and human disease,” said Michael Yost, DEOHS professor and chair.

Insights from “the white rat of the fish world”

Gallagher first came to the UW as a postdoctoral researcher with DEOHS Professor Emeritus David Eaton in the 1990s. There, he helped uncover why humans and some other animals are susceptible to aflatoxin, a carcinogen produced by fungi and found on crops such as corn.

As a faculty member at the University of Florida, and later at the UW, he focused on how biochemical pathways in fish from catfish to salmon might protect them from exposures to chemicals in the environment, including the pesticide chlorpyrifos. During this time, he also studied the effect of development on toxicant injury in humans.

In recent years, he and his colleagues used zebrafish, which he calls “the white rat of the fish world,” to address a wide range of environmental and human health questions.

“His work has helped contribute to understanding the critical role of olfaction on salmon migration and how wastewater discharges of metals, pharmaceuticals and other pollutants can damage the sensory pathway, altering behaviors and survival of fish and mammals such as orcas,” Yost said. “The parallel mechanistic changes in human olfaction now also have grown in prominence as early indicators of chemical impacts and disease.”

Gallagher credits research scientists in the Functional Genomics and Bioinformatics Core Laboratory, including Theo Bammler, Pat Janssen and Lu Wang, with helping him pioneer whole-genome technology in fish.

“UW and our department have really smart people and a tremendous collection of resources and technology,” he said. “It helped me do really interesting work that I may not have been able to conduct at another institution.”

Superfund superstars

As director of the Superfund Research Program, Gallagher collaborated with DEOHS faculty members including Lucio Costa, Clem Furlong and Zhengui Xia, whom he called “real leaders in understanding how metals and other chemicals might lead to dementia and other neurotoxic conditions.”

He is especially proud of how the program brought together scientists from diverse disciplines, including engineering, environmental sciences, human health and public health, to solve ecological and human health problems.

“When students working in the human health labs would come to group meetings and listen to what was going on with our environmental research, you could see them getting perked up by that, and vice versa,” he said.

Gallagher also joined forces with DEOHS Professor Emeritus Terry Kavanagh as part of a green chemistry consortium on designing safer chemicals, and with scientists at NOAA Fisheries to show how elevated carbon dioxide levels associated with climate change affect salmon’s sense of smell.

Learning from mentees

Gallagher has enjoyed mentoring 12 postdocs and several graduate students over the course of his career, as well as teaching many students in his courses.

In the past decade, he has felt lucky to work with “a really smart group,” including research scientists Richard Ramsden and Mike Espinoza, as well as former postdocs Chase Williams, Margaret Mills and Eva Ma, who introduced CRISPR gene editing technology into his zebrafish research to answer emerging ecological and human health questions.

“I realized that they were teaching me more than I was teaching them, as far as moving the science forward,” he said.

Gallagher is excited that Yijie Geng, a new assistant professor in DEOHS, will inherit his zebrafish lab and take it in a new direction: investigating the molecular basis of social behavior in health and diseases. Gallagher will continue serving on committees and lecturing as an emeritus professor.

During retirement, he hopes to return to two passions he had less time for as a faculty member: music and fly fishing.

“I’m looking forward to getting back into guitar, and maybe playing with a band again, because that was really the most fun period of my life,” he said.