“When I explain my thesis project to people, they are always excited to hear about me working with marine animals,” Alexandria Vingino said. “And then I explain to them that I'm not really working with marine animals, I'm working with what’s in their poop.”

But that poop—collected from harbor seals, river otters and fish in Puget Sound and the rivers that feed it—is full of information about how human activity influences the ecosystem and how antibiotic resistance could spread in the environment.

Vingino, an MPH student in One Health in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS), and her collaborators have found that some of these seals and river otters carry antibiotic-resistant strains of the bacteria Escherichia coli. Pathogenic forms of E. coli can cause troublesome drug-resistant infections in people, including urinary tract and blood infections.

Researchers don’t know yet whether these antibiotic-resistant strains affect marine wildlife directly. But their presence is concerning.

“It's eye opening: how could an animal that doesn't use antibiotics already have bacteria that are resistant to those antibiotics?” Vingino said.

Getting an early start

Vingino officially began her master’s program last September, but she got in touch with her adviser, DEOHS Professor Marilyn C. Roberts, as soon as she moved to Seattle the previous spring, hoping to get her feet wet.

Roberts and her colleagues had just received a grant to explore a concerning finding: they discovered antibiotic-resistant strains of E. coli in orca poop. These strains are part of a group of E. coli that cause urinary tract and other infections in humans and some animals, and related to those that cause disease in birds.

Where were these strains coming from, and how might they move around in the environment? DEOHS Professor Elaine Faustman and others had previously identified hotspots of bacterial genes that confer antibiotic resistance near the discharge of wastewater treatment plants and aquaculture operations in the Salish Sea, which includes Puget Sound and waters surrounding the San Juan Islands, as well as the Straits of Georgia and Juan de Fuca.

“We believe that the antibiotic-resistance genes originate from people or their activities and waste,” Roberts said.

Once these genes are in the water, they can spread by hopping between bacteria, and end up in the waste of animals who call these waters home.

Testing the waters

To figure out where these resistance genes go, Vingino quickly began work with the Washington State Department of Health’s Public Health labs in Shoreline to analyze E. coli isolated from water samples taken throughout the Salish Sea, as well as from wildlife fecal samples taken by researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, PAWS, Marine-Med and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

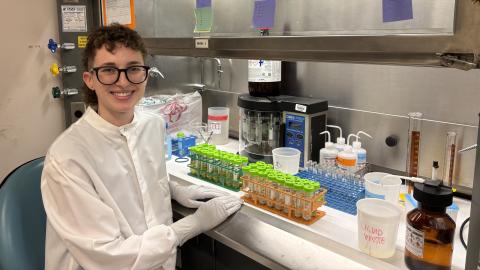

Vingino tests these samples for antibiotic resistance by isolating and growing E. coli in plates with varying concentrations of the drugs. Then she prepares samples for whole-genome sequencing, which tells the researchers how closely different E. coli strains are related to one another, and what virulence genes they may carry.

“She’s just really great to work with,” Roberts said of her student. “She's very committed, and she's doing really good work mapping the data, so that we can see where our drug-resistant strains are, as well as those related to human disease.”

So far, the researchers have found that the mammals they are studying are more likely to carry drug-resistant E. coli than the water samples.

“This may be because these animals carry E. coli in their guts, while E. coli does not survive long in marine waters,” Roberts said.

From One Health to COVID-19

For Vingino, the project is emblematic of her program’s One Health approach, which focuses on the links among humans, animals and the environment.

“It's definitely an interesting way to connect animals and humans,” she said. “We both poop, so how much similarity are we going to see in what's in there, based on the ecosystem we share?”

She has just finished her first year in the program, but she is already thinking about continuing her career in One Health, perhaps with a nonprofit like EcoHealth Alliance.

In the meantime, she is spending this summer on a more human-focused project: contact tracing for COVID-19. She is involved in a Snohomish County study testing whether having a contact tracing team inside an emergency room could help minimize cases in the county.

“It has been an engaging job and a good reminder that social distancing, wearing masks and washing hands are important measures to take to protect the community,” she said.

Other collaborators on the project include Dr. Peter Rabinowitz, professor in DEOHS and director of the Center for One Health Research (COHR); DEOHS Research Scientist David No; Lauren Frisbie, data analyst and manager for COHR; Dr. Scott Weissman, Seattle Children’s Hospital; Jeff Lahti, Shelley K. Lankford, Roxanne Meek, Philip Dykema, Ryan Ruiz and Dr. Marisa D’Angeli, Washington State Department of Health; Dr. Bethany Groves, PAWS; Dr. Stephanie A. Norman, wildlife veterinary epidemiologist and owner, Marine-Med, and affiliate instructor in UW Epidemiology; Dr. Michelle Wainstein, field conservation associate, Woodland Park Zoo; Dr. James E. West, Marine Resources Division, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife; Dyanna Lambourn, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife; and UW Microbiology Professor Dr. Evgeni V. Sokurenko.