Countries including the US are taking dramatic steps to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus, with some barring entry to anyone who has recently visited China.

But do travel bans work?

Very little research exists, and the evidence available suggests any benefit may be temporary, according to a new study led by Nicole Errett, lecturer in the University of Washington Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences, and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University.

The research was published in January in the Journal of Emergency Management.

We asked Errett to explain why international travel bans may do more harm than good and what countries should do instead.

You reviewed more than 2,000 research articles and found just six studies that explored the use of international travel bans to control the spread of emerging infectious diseases. What did you learn?

We looked at four infectious diseases that have emerged in recent years—the Ebola virus, SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) and the Zika virus (we did not include other infectious diseases, such as influenza).

We found only a handful of modeling studies on Ebola and SARS, and nothing that evaluated the impact of an actual ban after it was implemented.

Some of the evidence suggests that a travel ban may delay the arrival of an infectious disease in a country by days or weeks. However, there is very little evidence to suggest that a travel ban eliminates the risk of the disease crossing borders in the long term.

Our ability to draw conclusions across the different studies we reviewed was limited by the small number of relevant studies. We urgently need more research in this area to understand whether travel bans and other control measures are truly effective.

Countries including the United States, New Zealand and the Philippines have imposed travel bans in response to the emergence of the new coronavirus in China. What’s the harm in using travel bans to combat infectious diseases?

The economic and social impacts on countries are profound, and we’re already seeing the effects.

China’s economy is taking a huge hit, with a ripple effect felt around the world. Airports and borders are closed, supply chains are interrupted, businesses are shuttered.

Health and health systems are also affected, as it becomes difficult to transport health care workers and resources where they are needed, and people avoid or can’t access routine health care services.

The stigma associated with travel bans sparks xenophobia and racism, and we’re already seeing that play out in the US and other countries.

Why has so little research been done on travel bans?

Assessing the impact of a real-world travel ban is challenging.

Travel bans are often implemented alongside other travel restrictions and control measures. It’s really hard to tease apart the impacts of travel bans versus other outbreak response measures.

The studies we found are all based on models and simulations, and most focused only on air travel without considering land or sea crossings.

The models rely on assumptions, and they don’t fully account for things like human behavior. For example, people may voluntarily reduce their travel or change their modes and routes of transportation.

The studies we found modeled the impacts of travel bans on Ebola and SARS, specifically. Every disease has unique characteristics, including the modes and rate of transmission and how sick people get once they’re infected.

Social and environmental circumstances also influence how a disease is transmitted. Together, all of these factors have an impact on how or if control measures work. This makes it difficult to apply the conclusions from any given study to the novel coronavirus.

What should countries do instead?

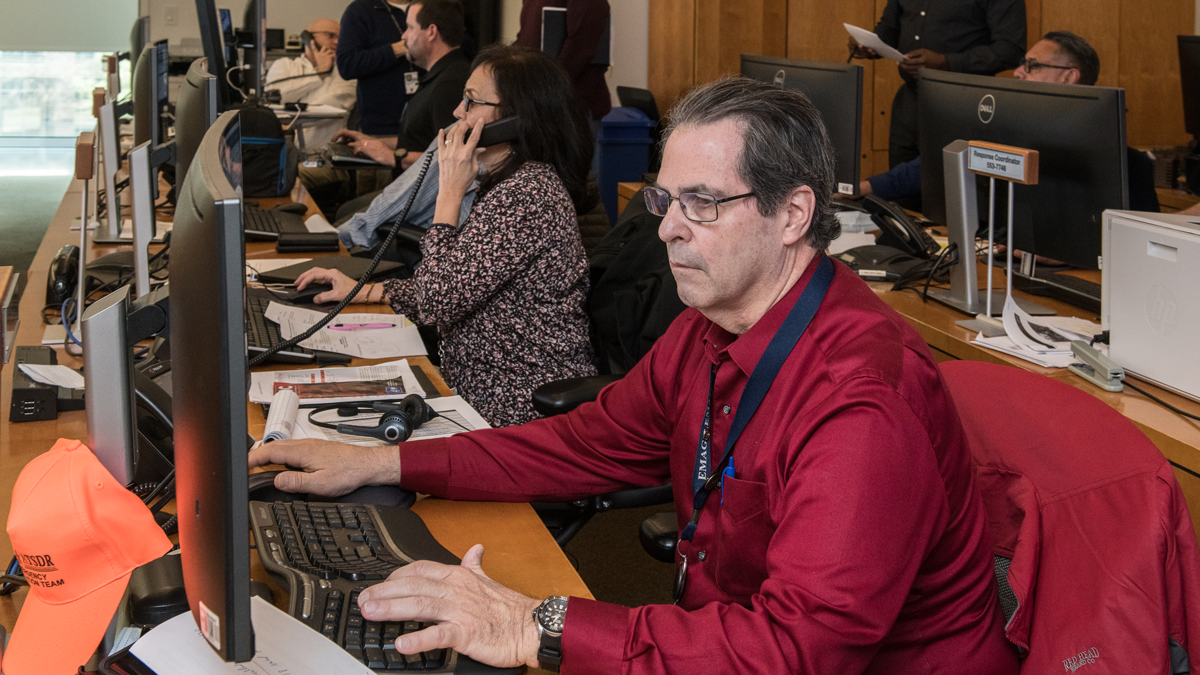

We should focus on the things we know are effective—vaccine development, domestic travel screening, patient monitoring, clear risk communication and investing in public health systems that work and are ready to respond to emergencies.

Following the Ebola crisis, the US and many countries focused on strengthening their health systems so that all types of hospitals were more prepared to respond in an emergency.

In the case of the coronavirus, an effective global response should start with bolstering China’s own response to the epidemic within its borders and preparing health systems around the world to deal with a potential outbreak.

What can we learn now in the face of the coronavirus to strengthen our response in the future?

Until more evidence is available, policymakers should use extreme caution in applying travel bans as a policy solution to control the spread of disease.

Those of us involved in disaster preparedness research and policy need to start thinking now about how to measure the effectiveness of emergency response measures such as travel bans to inform future response efforts. We need protocols in place beforehand so that we can gather and share data in a consistent way.

It’s not an “if” for the next event. It’s a matter of when. That’s a certainty.

And each event is an opportunity to improve our capability to respond to the next one. I think we will learn things from the coronavirus epidemic that can better prepare us for the future.

The study was co-authored by Lauren Sauer, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine; and Lainie Rutkow, Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins University.