My PhD adviser approached me with an unexpected opportunity in June 2020. A colleague in Portugal was looking for students to study at his university in Lisbon as part of the US Fulbright Student program.

This was something I had never considered. But completing a year of my PhD in Lisbon was not a chance I was going to pass up.

Shortly after that first meeting with UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) Professor Scott Meschke, I started thinking about health problems that affect people in both Seattle and Portugal.

My PhD research has concentrated on tracing the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. Although global public health problems are more apparent because of COVID-19, eventually this pandemic will end and we will have other health problems.

So I decided to focus my Fulbright project proposal on another serious threat to public health—bacterial resistance to antibiotics and the spread of antimicrobial resistance in the environment.

In September, I flew to Portugal to start my research at the Instituto Superior Técnico.

Investigating antimicrobial resistance

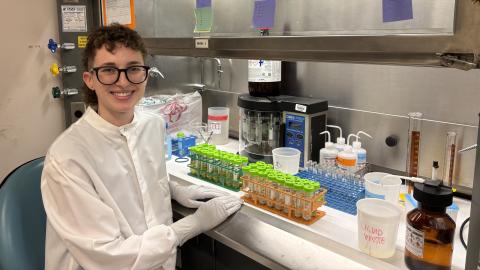

During my Fulbright, I’m characterizing antimicrobial resistance over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic and in different seasons using wastewater samples.

Why wastewater? Antimicrobial resistance can be spread when microbes exchange genes in wastewater and other water sources, putting people at risk for drug-resistant infections. We can track the spread by measuring different antimicrobial-resistant genes in the water.

We can also get an idea of the antibacterial resistance associated with a community, because wastewater serves as a composite sample of everyone in the community.

My new research group helped the Portuguese government look for the SARS-CoV-2 virus in wastewater collected all over the country. I plan to test some of these frozen samples for different antimicrobial-resistant genes and to test wastewater over the coming months for the same genes.

Because antibiotics are frequently prescribed for respiratory infections, I am curious to see whether increases in antibiotic resistance correspond with seasonal respiratory infections of COVID-19 and other diseases.

Once I return to Seattle, I plan on conducting similar experiments using Seattle wastewater.

“It is crucial to build international collaborations to be better prepared for future threats to public health.”

- Sarah Philo

A global view

I hope my project will help provide a better global picture of antimicrobial resistance. A few weeks ago, I completed my general exam focused on this topic, setting me up to finish my PhD in 2023.

If there is one thing I have learned from the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s this: Infectious diseases can rapidly spread around the world before we fully comprehend what is happening.

It is crucial to build international collaborations to be better prepared for future threats to public health. The Fulbright Program is well suited to foster these relationships because of its established support system.

My project is helping to advance these collaborations because there are very few trans-Atlantic antimicrobial resistance studies and I am working closely with different research groups and public utilities.

Exploring Portugal

I’ve also had the time to explore and appreciate Portugal in my free time. I spent my first week getting oriented in Lisbon and meeting other “Fulbrighters” before we went off to our different host universities.

From the beginning, the people I’ve met here have been so welcoming and patient with my (very beginner) Portuguese language skills. I spent a weekend in Porto with other Fulbrighters and have tried to see a different Lisbon neighborhood each weekend.

I recently visited the town of Belém, where the Jerónimos Monastery and Belém Tower are located. Sailors would visit the monastery before departing to pray for safe passage, and the tower was one of the last views they had of Europe.

Reckoning with history

These incredible buildings are integral to Portugal’s complicated history. Starting in the 14th century, their navy explored the world and helped establish maritime trade routes with India and other parts of Asia through sometimes-violent colonization and treaties.

The Portuguese also infamously launched the trans-Atlantic slave trade. During the Fulbright Program orientation, we went on a walking tour of Lisbon that focused on the history of Africans in the city.

It was good to hear that people are starting to recognize their country’s role in the horror of slavery. However, it is clear they, like Americans, have a long way to go to fully reckon with its history.

A goal of the Fulbright program is to improve intercultural relationships between Americans and others across the world. I’m excited to get to know more of the Portuguese people, culture and history over the next six months, and I hope I can help bring a deeper understanding of American culture to people I interact with.