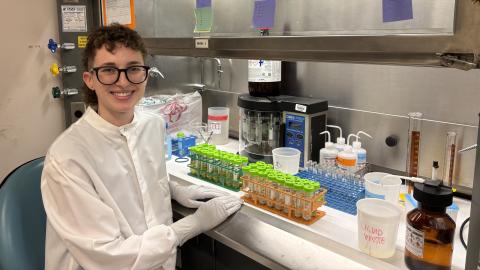

Viviana Albán

PhD, Environmental Health Sciences

Hometown

Ambato, Ecuador

Future plans

Pursuing an academic position in environmental health in Ecuador.

“I have found so much support through my adviser, but also from the postdocs, PhD students, staff and collaborators in her lab.”

-Viviana Albán

In small towns and rural villages in Ecuador’s northern coastal province of Esmeraldas, many kids grow up surrounded by animals. Families often raise chickens and pigs in their backyards, and some also have cows, horses, dogs or parrots.

Though the experience of growing up around animals can be enriching, public health researchers are also concerned that kids can get sick after being exposed to pathogens in animal poop.

“It’s a high-transmission setting for enteric pathogens,” or pathogens that cause intestinal illness, said Viviana Albán, a PhD student in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) working in Professor Karen Levy’s lab.

In a recent study by Levy and collaborators, 89% of a cohort of 276 6-month-olds in northern coastal Ecuador had at least one of these enteric pathogens — bacterial, viral or parasitic — in their stool.

Now Albán is working with a related cohort in Esmeraldas to investigate how much the children’s exposure to animals influences their gut health. She recently won a Russell L. Castner Award to support next-generation sequencing that will help her explore associations between animal exposure and children’s gut microbiomes.

Microbes on backyard farms

Albán started this research during her master’s in microbiology at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador. Along with Levy and others, she worked with a cohort of children from birth to 2 years old in Esmeraldas, collecting samples of poop from the animals in their households.

_sm.png)

In that pilot study, Albán found that 40% to 70% of animals in the children’s households —including chickens, pigs, cows, horses, dogs and parrots — had enteric pathogens in their feces.

Because antibiotics are frequently given to livestock in Ecuador to fight infection and encourage growth, there is also a risk that antibiotic resistance genes in animal feces could be transmitted to kids, making bacterial infections harder to treat.

“Animals can transmit these microorganisms, and all other gene content that comes with those microorganisms,” she explained.

Illuminating kids' microbiomes

To explore animal fecal contamination in the household environment, Albán is testing five different molecular markers in environmental samples.

These microbial source tracking (MST) markers can tell her whether the fecal contaminants she finds are human, avian, canine, swine or ruminant in origin. Together with that information and survey data from the families, she’ll determine whether kids in the cohort have low, intermediate or high exposure to animals.

Next, she’ll compare kids’ level of animal exposure with the presence of different enteric microorganisms and antimicrobial resistance genes in the children’s stool.

With the Castner funds, Albán will expand her current microbiome approach to use a cutting-edge approach called shotgun metagenomic sequencing. The newer technique will allow her to understand more about the function of genes within the gut microbiome of these kids, including antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes.

Solutions with sensitivity

As Albán waits for her results, she already has ideas for targeted interventions that could help reduce kids’ exposures.

She is interested in developing approaches to educate families on how pathogens and genes can spread from animals to people, as well as encouraging community-based spaces where families could raise animals separately from their home environments.

The spaces could make sure people “don't lose the fact that they depend on these animals, but allow them to raise the animals under controlled conditions” that improve sanitation and reduce the spread of disease, she said.

An interdisciplinary department

After working with Levy on her master’s in Ecuador, Albán was drawn to pursue her PhD in DEOHS because of her desire to combine her background in microbiology with her passion to improve public health.

“It was the perfect fit,” she said. “I feel like I'm doing something for society, and I'm doing something for communities back home.”

What’s more, the interdisciplinary nature of the department means she discovers new topics in environmental health nearly every week — particularly through the department’s weekly Environmental and Occupational Health Seminar series.

She has also appreciated the chance to learn from the other members of Levy’s research group, which includes epidemiologists, microbiologists and biostatisticians, and to build up her own epidemiological and biostatistical knowledge through classwork.

Finally, she cherishes her cohort of fellow PhD students, who support each other through a weekly writing group and other activities.

After graduation, Albán hopes to pursue a career in Ecuador as a professor in environmental health.

“It is really my hope to go back home and keep working with communities, and students too,” she said. “I would love to apply everything that I've learned in this program.”