How many grams of feces does the average human excrete each day?

That question—part of Erica Fuhrmeister’s first college research project as an undergraduate at Johns Hopkins University—might have sent some budding scientists running for the nearest liberal arts course.

Yet the project hooked Fuhrmeister on science and helped open the door to a career at the intersection of public health and environmental engineering that is still animated by questions related to microbiology and water sanitation. (By the way, the answer to that question is 128 grams, or about a half-cup.)

“People have produced waste as long as we have existed. It’s mind-boggling to me that in the 21st century, we still can’t protect everyone from those pathogens,” she said. “It speaks to the complexity of the issue.”

Fuhrmeister is a new assistant professor in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS) whose research focuses on antimicrobial resistance, the microbiome, One Health and ways to protect people from pathogens that cause diarrheal disease and other illnesses.

She is also an assistant professor in the UW Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering.

From shore birds to goat poop

It was on a high school trip to the Jersey shore where Fuhrmeister saw for the first time how her interests in science, the environment and engineering could combine.

Her environmental science class went to the shore to count birds, a citizen science project that piqued Fuhrmeister’s interest in how data could be used in conservation work. She was also influenced by her father, a nuclear engineer, and a natural interest in problem-solving and practical solutions.

After earning her BS in environmental engineering, she headed to the University of California, Berkeley, to earn a master’s and a PhD in civil and environmental engineering.

Her PhD project examined the environmental health impact of improving sanitation services in rural Bangladesh.

During a visit to Bangladesh, she remembers collecting animal feces from a study site and attracting a crowd of laughing children, “like what is this white lady doing here, picking up our goats’ poop?” Fuhrmeister recalled with a laugh.

She found that pathogen transmission through animals was a significant issue that needed more attention. “Just providing a better pit latrine on a property wasn’t enough to reduce exposure. What about sanitation at the school, at the neighbors? How about animals that are on the property? Now we think about sanitation more holistically.”

Finding practical solutions for better health

Her training as an engineer pushes her to find practical solutions, she said. “It’s not about coming in with a fancy new toilet design. What’s the lowest cost, what’s the most feasible way to do something?” she said.

“And how can we motivate communities to make changes in a way that protects their health and is also good for the animals they are raising?”

She also spent time with Bangladeshi scientists in the project lab. They asked her why the samples they were preparing had to be shipped to the United States for analysis, rather than allowing local scientists to take ownership of the work. Fuhrmeister didn’t have a good answer.

“I think about that a lot. What’s our role as outside researchers in foreign contexts? How can we build local capacity and increase opportunities for local scientists to collaborate or conduct independent research?” Fuhrmeister said.

“It’s the people who live there who have the answers, not us.”

Sequencing DNA to understand antimicrobial resistance

After earning her PhD, Fuhrmeister landed a postdoctoral fellowship at Tufts University in the middle of the “sequencing boom,” she said, with new technologies allowing sophisticated testing of DNA in samples.

She became interested in antimicrobial resistance and what happens when a pathogen becomes resistant to treatment options.

That work took her to Kenya, where she worked on a research project to understand the transmission of antibiotic resistance genes between humans, animals and the environment in Nairobi.

Her current work focuses on the significant overlap between human and animal antimicrobial resistance and how reducing antibiotics in animal feed or in veterinary prescriptions could help reduce antimicrobial resistance for both.

She is working with partners on a project to understand antibiotic usage in agriculture and veterinary medicine in Washington state, collaborating with the state Department of Health and the UW Center for One Health Research, part of DEOHS.

She is also developing bioinformatic tools to assess the health risks of antimicrobial resistance within microbiomes. That work is funded by the UW Center for Exposures, Diseases, Genomics and Environment, also part of DEOHS.

“Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) or superbugs come up often in the media, yet there are a lot of misconceptions about what these terms mean. Engaging with the public about AMR provides an exciting opportunity to get communities involved as stakeholders in a global problem,” she said.

Opening doors through mentorship

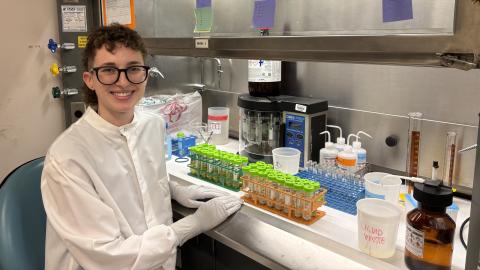

As Fuhrmeister enters her second academic year at the UW, she still considers herself “in startup mode,” with a lab that is literally under construction and a roster of lab members that is slowly filling up.

She credits her career trajectory to the mentoring she received from faculty and postdoctoral scholars along the way, and she makes it a point to include undergraduate students in her research (she is currently mentoring two DEOHS undergrads and one graduate student).

One of her favorite things about being at the UW is the cross-campus collaboration. “The UW takes the idea of community-based research to heart, and I have enjoyed opportunities to connect with colleagues across campus, at the state Department of Health and in the community,” she said.

She recently finished writing a research proposal to the US EPA that involved faculty across three different UW schools to investigate how different wastewater treatment processes impact AMR transmitted into the environment.

“I was impressed with the fact that we could get all of that expertise from within the UW,” she said.

Settling into the Pacific Northwest

When she’s not in the lab, Fuhrmeister enjoys hiking with friends and baking with her husband, a UW chemical engineering professor. She also is trying her hand at gardening.

“It’s my first year of planting seeds, and then suddenly you have zucchini! You don’t usually get that kind of instant gratification as a scientist,” she said.

Fuhrmeister also admits to being a foodie. “Food is a destination for me,” she said. “I can be convinced to travel far if I hear you’ve got to try this cake place!”