Ola i ka Wai. Water is life.

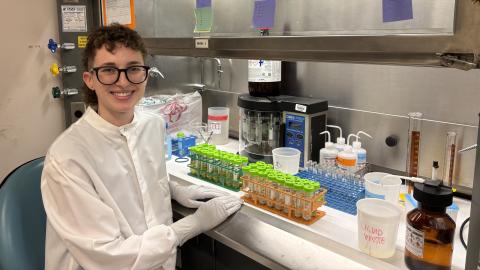

Tyler Gerken

MS, Environmental Health

Hometown:

Kea’au, Hawai’i Island, HI

Future plans:

A career in the US Public Health Service, perhaps as an environmental health officer for the National Park Service or the Indian Health Service

Quote:

“To care for a place, you need to really love that place and . . . have this greater understanding and awareness of where you are.”

This Native Hawaiian proverb runs like a current through Tyler Gerken’s life.

The University of Washington student grew up in a lowland rainforest on Hawai’i’s Big Island that gets up to 100 inches of rain a year. His great-great grandmother was a Kahuna La’au Lapa’au—a Native Hawaiian medicinal plant priest—who crafted medicines from hundreds of different herbs and plants.

Initially, Gerken followed in the footsteps of many of his relatives in the nursing field by becoming a certified nurse’s assistant. But it wasn’t the right fit for him. For one thing, it involved spending too much time inside.

Now a master’s student in Environmental Health at the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS), Gerken combines his love for the natural world with his concern for others.

“I want to improve the health of the environment so that all people can benefit from an increased quality of life,” he said.

Tracing a threat to Hawaiian swimmers

Gerken recently won one of six master’s fellowships from the UW School of Public Health. The $20,000 award will fund his thesis research on a threat to health and clean water in Hawai’i: pathogenic bacteria in coastal waters that can cause serious skin infections for swimmers and surfers.

Hawai’i has some of the highest rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections in the US.

MRSA can infect swimmers with open cuts, leading to skin sores that can develop into more serious internal infections. Children, Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders are particularly susceptible to staph infections such as MRSA.

The path to DEOHS

Gerken began studying MRSA and other pathogenic bacteria as an undergraduate at the University of Hawai’i at Hilo with Professor Tracy Wiegner.

Their project got the attention of DEOHS Professor Marilyn Roberts, an expert on MRSA, during a visit to the University of Hawai’i.

Gerken’s conversation with Roberts inspired him to continue his research in the MS program at DEOHS.

Why so many MRSA cases?

For his thesis, Gerken will work with Roberts and Wiegner to characterize strains of MRSA on the Big Island—something that has never been done before—hoping to explain why there are so many cases of MRSA in Hawai’i.

One possibility is old cesspools that remain in use because of the challenge of connecting rural communities to sewer lines. There are almost 49,000 cesspools on the Big Island with about 8,700 in Hilo, and they leak millions of gallons of untreated wastewater into the ground each day. This sewage can also contaminate coastal waters.

Gerken will sample beaches, rivers and wastewater in the Hilo Bay watershed later this year and determine what strains of MRSA are in the water.

One of his research sites is a community of homes for Native Hawaiians located near a sewage treatment plant, where residents are concerned about bacterial infections.

Community-acquired vs hospital-acquired MRSA

Gerken hopes to uncover factors related to antibiotic resistance and virulence associated with the MRSA strains he samples and piece together their epidemiological evolution.

MRSA strains that cause infections in swimmers, called community-acquired MRSA, tend to be more virulent but less resistant to antibiotics than those that cause hospital-acquired infections.

To compare the two, Gerken will also analyze MRSA strains collected from clinical patients.

His findings could assist public health experts monitoring for new strains that can cause community outbreaks and help doctors tailor treatments for MRSA.

A sense of place

Native Hawaiian traditions and ecological knowledge also inform Gerken’s research.

When he does fieldwork, he practices the Native Hawaiian custom of stopping first to listen and acknowledge the environment, both past and present.

Once, he began chanting before sampling in a Hawaiian forest, with the winds blowing fast. Almost immediately, a six-foot tree branch landed a few feet away from him. “That was a signal that it was not the right time to enter the forest,” he said.

He waited for about an hour. When the wind stopped, he chanted again. Once it felt right, he went back into the forest.

Looking ahead

Gerken returned to the Big Island last month to start his fieldwork. But the University of Hawai’i at Hilo has paused active research because of COVID-19, so for now, he is planning his water quality sampling design.

“Seeing that I can make a big difference in my local community is the biggest driver for me,” he said.