DEOHS is collaborating with cross-sector partners to prepare for a hotter future in the Pacific Northwest

Dr. Jeremy Hess had just started his night shift in Harborview Medical Center’s busy Emergency Department when he noticed a patient on a gurney. The man was wrapped in a sheet with his feet sticking out.

“He had severe, third-degree burns on the bottom of his feet from walking barefoot on the pavement,” Hess recalled. “It was dramatic, and it was clear this was going to affect his mobility.”

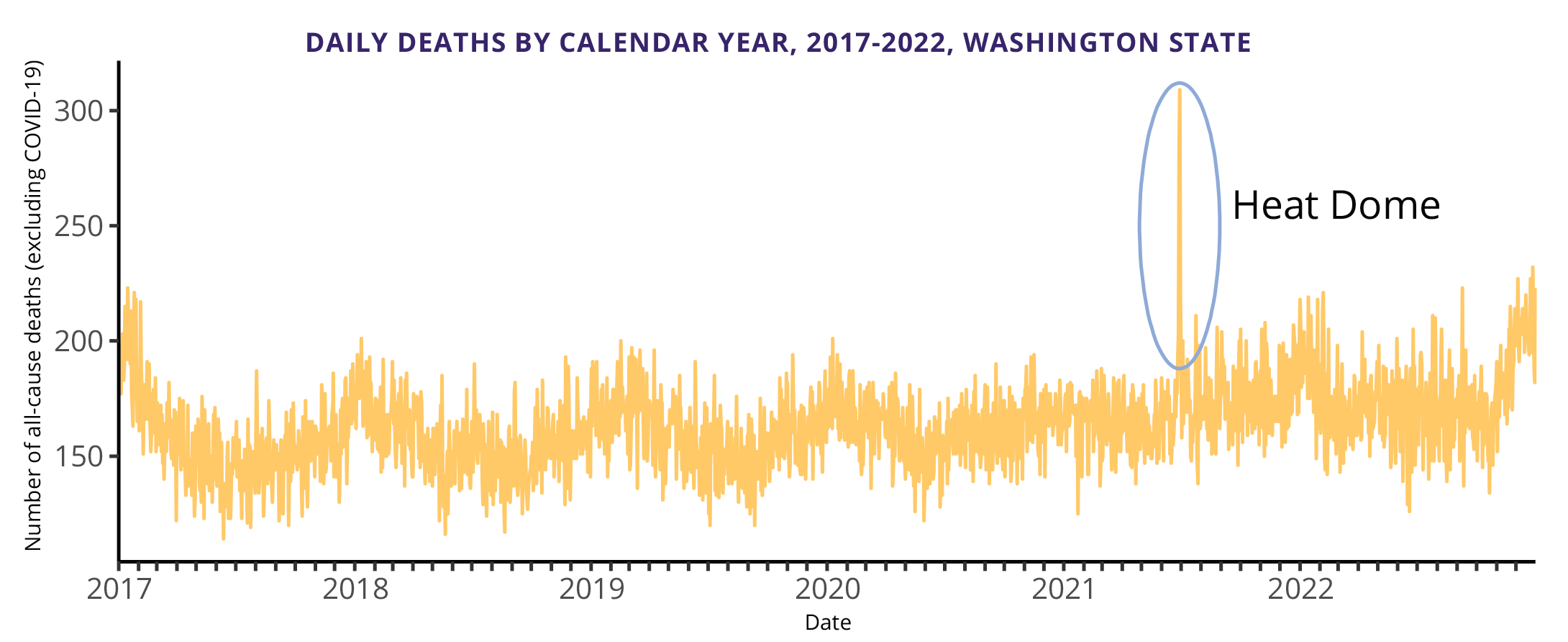

That day, June 28, was the peak of the deadliest weather-related event in Washington history: the 2021 heat dome, when a historic heat wave swept over the Pacific Northwest, leaving hundreds dead.

Temperatures reached 108°F in Seattle and 116°F in Portland that day. Seattle-King County 911 received its largest volume of calls since the system launched in 1968.

Over a seven-day period, Washington officially counted 119 deaths directly related to the heat, though other estimates were higher. A recent UW study identified an additional 159 heat-related injury deaths across Washington in the three-week period during and after the heat dome.

Ambulances backed up outside hospitals with patients suffering from heat illness, burns, cardiac and kidney issues waiting for beds. Hospitals cooled down patients in body bags filled with ice.

“Imagine showing up at an emergency department and being placed in a body bag,” said Nicole Errett, assistant professor in the University of Washington Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS).

“There were these creative and innovative solutions, but what could we do with more forethought and planning and intentionality to this?”

Our future will be hotter

It may be comforting to think of the 2021 heat dome as an event so extreme, it could never happen again. But that’s the wrong takeaway, said Hess, a DEOHS professor and emergency medicine physician.

“We need to recognize that this is certain to happen again,” Hess said. “These events are becoming more likely, they’re dangerous, and places like ours that haven’t experienced extreme heat are particularly at risk.”

The state’s aging population, increasing urbanization and climate change mean more Washingtonians will be vulnerable to future heat events.

“These events are becoming more likely, they’re dangerous, and places like ours that haven’t experienced extreme heat are particularly at risk.”

–Dr. Jeremy Hess

To get ready for a hotter future, Washington urgently needs to prepare now.

Hess, Errett and other DEOHS researchers are leading cutting-edge research, creating new tools and building partnerships to help Washington and the Pacific Northwest get ready for what is coming.

Solutions: Preparing for a hotter future

Solution: Identify those most at risk

How to save lives from extreme heat

Source: Vogel J, Hess J, Kearl Z, Naismith K, Bumbaco K, Henning BG, Cunningham R, Bond N. 2023. In the Hot Seat: Saving Lives from Extreme Heat in Washington State.

Where you live, your age, your health, your work: All of these influence your risk of suffering health effects from extreme heat.

Those most at risk include: elderly people, pregnant people, people with chronic medical conditions, people from low-income households or those experiencing homelessness or living in substandard housing, people who work outdoors or participate in outdoor sports and those who are not fluent in English.

DEOHS-led research has shown that extreme heat leads to increases in calls for emergency medical services, hospitalizations and deaths across Washington, including in King County and other regions that typically have milder climates.

Other DEOHS-led research has found unexpected risks in younger age groups from extreme heat.

A study led by DEOHS Teaching Professor Tania Busch Isaksen found an increased relative risk of hospitalization at all ages, particularly for kidney-related issues and natural heat exposure. The study team found effects on health outcomes in age groups as young as 15 to 44 years old.

Those living in urban “heat islands” with lots of asphalt, few trees and little air conditioning also face increased risk.

Communities that lack effective municipal heat action plans, heat early-warning systems, targeted risk communication and surveillance for heat-related illness and deaths are also more vulnerable, said Hess, who leads the UW Center for Health and the Global Environment (CHanGE), part of DEOHS.

Last month, CHanGE, the UW Climate Impacts Group and UW EarthLab launched a new report, “In the hot seat: Saving lives from extreme heat in Washington state,” along with co-authors from the state Department of Health, the Office of the State Climatologist and Gonzaga University.

It shares practical steps to reduce the health risks of extreme heat by a range of entities, from local health jurisdictions and parks departments to state agencies and community-based organizations.

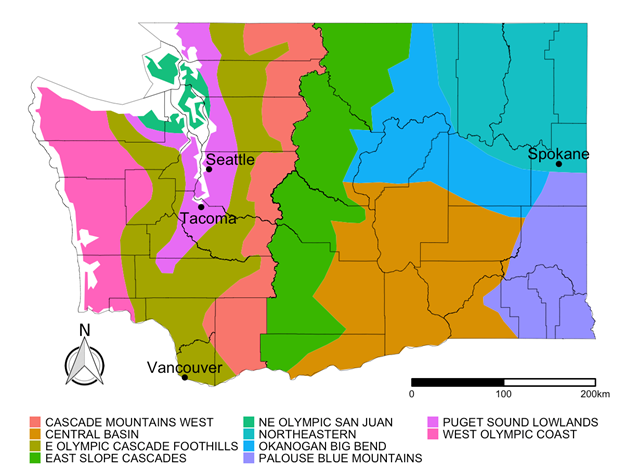

CHanGE also launched a new climate health risk mapping tool designed to help decision-makers identify high-risk communities, make evidence-based decisions in an emergency and find suggestions for short- and long-term risk reduction strategies.

The tool shows heat health risks at the census-tract level across Washington. CHanGE is seeking additional funding to scale up the tool to include data from the US and other countries, Hess said.

Watch Dr. Jeremy Hess demonstrate the new Climate Health and Risk Tool developed by the UW Center for Health and the Global Environment and discuss the June 2021 heat dome. The tool helps identify Washington communities at high risk during heat events and pinpoint specific solutions to help protect health, from improving communications about heat risks to increasing tree canopy and shade structures.

Solution: Partner with vulnerable communities

Not all Washingtonians experience extreme heat the same way.

The legacy of racism, redlining and social and economic disparities mean some communities face more risk than others.

That could be seen clearly during the 2021 heat dome, when hospitals strained to manage the intense surge in patients with heat-related illnesses, Hess said.

Valley Medical Center in Renton was among those most affected and came close to running out of ventilators, with a fivefold increase in the typical number of patients in their intensive care unit.

“We were severely unprepared for the number of patients we were going to see,” said Dr. Cameron Buck, emergency medicine physician with UW Medicine/Valley Medical Center.

Many of the hospital’s patients came from low-income communities and adult family homes around Sea-Tac Airport and other areas considered urban heat islands where the temperature never cooled off much at night.

Extreme heat is a top concern of members of two such communities, Seattle's South Park and Georgetown neighborhoods, according to a recent survey led by the Duwamish River Community Coalition, the Collaborative on Extreme Event Resilience (CEER) and partners.

Tailoring communications to reach vulnerable populations about the risks of extreme heat is essential, according to a recent study by Hess, Errett and colleagues. Errett is co-director of CEER, which is part of DEOHS.

They found that many US public health agencies rely on passive communications approaches, like social media and news alerts, to warn the public about extreme heat. But those channels may not reach the elderly, people experiencing homelessness and others most vulnerable to heat.

Instead, Errett suggests going back to basics: encouraging neighbors to help each other. In New York City’s Be a Buddy program, people sign up to check on their neighbors in hot weather.

She cited a famous example documented in the book Heat Wave. During the 1995 Chicago heat wave, which caused over 700 deaths, fewer people died in a close-knit neighborhood where people checked on their neighbors than in a socioeconomically similar one that lacked those social ties.

“We focus a lot on creating community cooling centers, but we can do a lot of good through our own social networks. Bring a neighbor over for a meal and get them out of the hot space for a bit," Errett said.

In another effort to reach vulnerable groups, Busch Isaksen partnered with Public Health – Seattle & King County to develop a comic drawn by artist David Lasky. It is now available in 12 languages to clarify heat risks and safety tips and recently won an award from the EPA.

Protecting outdoor workers

People who work in agriculture, construction, landscaping and other outdoor jobs also face unique risks.

DEOHS experts helped advise policymakers in Washington and Oregon on how to regulate work conditions for outdoor workers during extreme heat events.

The new permanent outdoor heat exposure rules adopted by the Washington State Department of Labor & Industries go into effect July 17, with added requirements for shade, cool-down rest breaks, training and other updates.

Research led by DEOHS Assistant Professor Elena Austin and colleagues found that Washington counties with the largest agricultural populations typically had the greatest exposure to the concurrent health threats of high heat and particulate matter generated by wildfire smoke.

Another 2020 study led by DEOHS Associate Professor June Spector and colleagues found that agricultural workers in the US will see unsafely hot workdays double by 2050 because of climate change.

Both Austin and Spector are affiliated with the Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health (PNASH) Center, part of DEOHS. The center offers a heat toolkit to promote workplace safety and health in agriculture, as well as other resources in both Spanish and English. These materials were recently recognized with an award from the US Environmental Protection Agency.

Farmworkers face special risks

“Unfortunately, heat and smoke happen at the same time that harvest happens, and workers are often paid at piece rate during that time,” said Maria Blancas, PNASH research coordinator.

PNASH partners with farmworkers, growers and public agencies to codevelop heat resources. For example, at last year’s Washington State Agricultural Safety Fair, they asked participants to vote on creative ways to convey the importance of taking time to acclimate to working in heat.

This year, they created a new infographic on preventing heat illness in agriculture to provide practical recommendations and highlight Washington state's new outdoor heat exposure rules for workers.

“It is important that workers know what their employers are required to provide and do,” Blancas said.

#BeHeatSmart campaign

Listen to this public service announcement aimed at outdoor workers in Eastern Washington on working safely in the heat. Credit: Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center (DEOHS) and Radio KDNA. Transcript in English and Spanish.

To get the information out, PNASH’s #BeHeatSmart media campaign highlights best practices for heat-related illness prevention in agriculture in collaboration with local, regional and national partners. The media kit includes radio messages in Spanish, customizable social media cards and training resources and tools in English and Spanish.

To further address farmworkers’ concerns, Blancas and Savannah D’Evelyn, a DEOHS postdoctoral researcher, are collaborating with central Washington nonprofit Wenatchee CAFÉ on a project funded by a grant from UW EarthLab.

Building on listening sessions the team led last summer with farmworker families, the team invited families to share their experiences with heat and wildfire smoke and create a community story using art at a workshop last month.

Later this summer, the team will convene workshops with public agencies and community groups in the region to share their findings and codevelop outreach resources to reach “unique, diverse communities where it's not a matter of if smoke and heat as much as a matter of when they'll be impacted by it,” Blancas said.

Solution: Build broad partnerships to save lives

The 2021 heat dome served as regional wake-up call for many, galvanizing elected leaders, health professionals, academic researchers and others to come together to plan for future extreme heat events.

DEOHS is helping to build those critical collaborations across the state and across sectors to make sure Washington is ready for the next heat event.

Errett and DEOHS Assistant Teaching Professor Resham Patel are partnering with Public Health – Seattle & King County to establish such a collaborative network, in a project funded by Urban@UW. They will convene public health practitioners, academics and community partners from Seattle; Portland, Oregon; and Vancouver, Canada, to discuss public health interventions prompted by the heat dome, including new mitigation strategies.

“The opportunity to collect these different perspectives and have synergistic effects is really exciting,” Patel said. “It’s a little bit of a Captain Planet moment.”

Across the state in Spokane, more than 40 community leaders gathered at Gonzaga University last month to talk about lessons learned from the 2021 heat dome and effective interventions and strategies for heat management. Attendees represented local government, fire and transit agencies, public health agencies, local media and community-based organizations.

The symposium was led by Busch Isaksen, who also co-leads CEER, along with Gonzaga's Brian Henning, and funded by the UW Interdisciplinary Center for Exposures, Diseases, Genomics and Environment, part of DEOHS.

“We are all in this together, and the only way we’re going to survive future events—quite literally—is to work together and help to build community resilience through meaningful connections.”

–Tania Busch Isaksen

“We are all in this together, and the only way we’re going to survive future events—quite literally—is to work together and help to build community resilience through meaningful connections,” she said.

Some of the discussion focused on how to protect people in precarious housing, including people living in substandard housing and renters who may be refused permission by landlords to install room air conditioners.

They also discussed the pros and cons of cooling centers—community gathering places where people can escape the heat. Some cities have found that few people show up, even when offered free transportation. Possible solutions include offering food and entertainment and allowing pets.

Other DEOHS-led research has examined the importance of public health preparedness for extreme heat events and analyzed heat action plans developed by local health departments and emergency management agencies.

One of the challenges in emergency response to heat waves is their relative invisibility compared to disasters like flooding and earthquakes.

“We don't see the damage, it's often happening to people in their homes,” Errett said. Most emergency response systems are activated by damage to physical infrastructure. In extreme heat events, "public health has a really big role, and they have been under-resourced to engage in this type of work,” Errett said.

Increasing staff and resources in health care and improving regional communication and planning are key needs for heat preparedness, according to recent findings by DEOHS MPH student Matias Korfmacher, Errett and collaborators. They conducted focus groups with health care and public health workers and other partners across the state in response to the 2021 heat dome, in partnership with the Northwest Healthcare Response Network.

Act now to save lives

Washington gets high marks overall for its investments in mitigating climate change, Hess said.

But with more heat waves and higher temperatures inevitable, “we need to be clear-eyed about the risks and how to move forward.”

He and other DEOHS researchers are also concerned about how prepared the region is for a potential double disaster—an extreme heat wave coupled with a massive power outage, or smoke from a wildfire event, as happened in Alberta, Canada, this spring.

Saving lives and protecting health in future extreme heat events will require both short-term emergency responses and long-term strategies, such as restoring tree canopy cover and building green roofs to reduce heat islands. Hess recently wrote about other ways to protect people from extreme heat in a Seattle Times op-ed with co-author Jason Vogel, interim director of the UW Climate Impacts Group

One example: “The most effective intervention is to increase the availability of air conditioning, which reduces the risk of mortality by about half,” Hess said. That kind of change is beyond the capabilities of any single institution and requires action on building codes, funding mechanisms and other complex system-level changes.

What we may not need is more study of the problem itself. “We’ve had 10 to 15 epidemiological studies on extreme heat prior to the heat dome,” Hess said. “We knew heat could kill people in Washington and result in injuries to workers.”

Hess sees similarities in how we have responded to other climate change-related events, like wildfire smoke and flooding. “Despite increased awareness, we haven’t put systems in place to anticipate and respond proactively,” Hess said.

“What we really need now is to implement the things that we know work and bring new partners together in this work.”

Tips to keep you safe and cool in the heat

To keep your body cool

- Stay hydrated.

- Take a quick, cold shower.

- Mist yourself with a spray bottle of cold water.

- Wear light-colored, lightweight, breathable clothing.

To keep your home cool

- Use a fan to pull in cool morning air.

- Turn on air-conditioning if you have it.

- Put a bowl of ice in front of a fan to cool the air.

- Close curtains to keep out the sun.

- Air-dry clothes instead of using an electric dryer. Cook outside when possible.

To stay cool outside

- Find or make shade in the yard.

- Turn on a sprinkler to mist off.

- Go to a public space with shade, air-conditioning and water (library, mall, community center).

Source: Pacific Northwest Agricultural Safety and Health Center/DEOHS. Transcript in English and Spanish

This web feature was produced by the DEOHS Communications team: Jolayne Houtz, Deirdre Lockwood, Veronica Brace and Zak Hussain.

Originally published July 2023

Photos: Seattle Center, Klod via Alamy, PNASH, CAFÉ, Tania Busch Isaksen, Unsplash, Jolayne Houtz