Editor's note: In January 2022, Anna Humphreys and colleagues, including DEOHS Assistant Professor Nicole Errett, published a paper in BMC Public Health on the impacts of rural wildfire smoke on mental health and well-being, and opportunities for adaptation. Read it here.

When Jake asked me to go on a sunset hike, I knew what was coming. We were in our favorite place: the Methow Valley of Eastern Washington. When we crested the top of the mountain, a few sunrays peeked through the clouds, lighting up the fertile valley below.

Still, when he got down on one knee, I was surprised, and overcome with happiness. Life seemed full of promise.

Later that summer of 2018, smoke from wildfires in the mountains around us filled the skies from the Methow to Seattle. I got a cough and felt constantly on edge. The claustrophobia cast a shadow on the future.

As Jake and I talked about having kids, I considered how much climate change would impact the world. I’d been a childbirth professional for a long time, and was so excited to become a mother.

Now, I looked at the world with a different lens—with less hope. I started to question my decision to have kids.

Action helps with grief. After I’d gotten through the worst of my anxiety, I switched focus in grad school from prenatal care to climate change. My capstone project in the UW School of Public Health and the Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences took me back to the Methow Valley and its smoky skies.

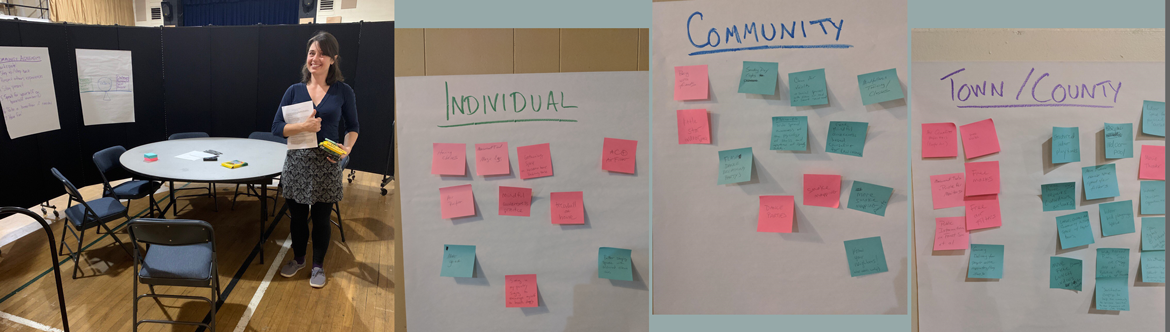

I interviewed residents about how they wanted to adapt to smoke events, which are becoming a new normal in the valley.

Most years, smoke stops regular life, keeps tourists away and hurts the economy. Events get canceled; people leave. Those who stay suffer: smoke harms the lungs and health in general.

Residents get stuck inside. Many people experience depression and anxiety. Community gatherings are one of the only sources of relief.

Nearly everyone I interviewed said they needed a clean-air community center where people could be together to weather the crisis.

But as COVID-19 has made a space like that impossible—at least for the time being—I questioned how to share my results. How could I communicate my findings without making people feel worse?

This summer, the Methow will probably have more smoke. Without the chance for community gatherings, the stress of wildfires may feel even more oppressive.

My final project includes a pamphlet for the public and a policy brief. For the pamphlet, I explained what people can do at home, including using or making air filters, calling friends and family, and finding time for light exercise and hobbies. I also mentioned community gatherings while stressing the importance of following COVID-19 precautions.

The policy brief pushes for increased mental health and educational resources and calls for funding a clean-air community space. Because pandemics don’t last forever. That’s the good news.

The bad news? Because of climate change, there’s no end in sight for smoke events. We need resilient communities to get us through the unknowns of the future.

As Jake and I continue to question whether we will indeed bring children into this world, the most hope we find is in how shared adversity unites people. We need to prepare communities for the coming disaster, even when it isn’t the immediate crisis. Future generations depend on it.

For her capstone project, Humphreys worked with community partner Clean Air Methow of the Methow Valley Citizens Council. DEOHS Assistant Professor Nicole Errett advised her on the project and Elizabeth Gribble (Walker), DEOHS affiliate assistant professor and director of Clean Air Methow, served as her site supervisor. Lisa Hayward Watts, communications manager for the UW Interdisciplinary Center for Exposures, Disease, Genomics & Environment (EDGE), designed the pamphlet. The EDGE Center Community Engagement Core funded pamphlet printing.