Rachel Wood is looking for TB’s missing millions. That’s what tuberculosis researchers like her call the 3 to 4 million people worldwide who have TB but have not been diagnosed or treated for the disease. One way they may be missed by healthcare systems is if they don’t have symptoms — a condition often called subclinical TB.

Some people with subclinical TB can still transmit the disease to others and are at risk of developing more serious symptoms themselves, or worse: TB is the leading cause of death worldwide from a single infectious agent.

“It’s important to find these people early” so they can get on treatment quickly, Wood said.

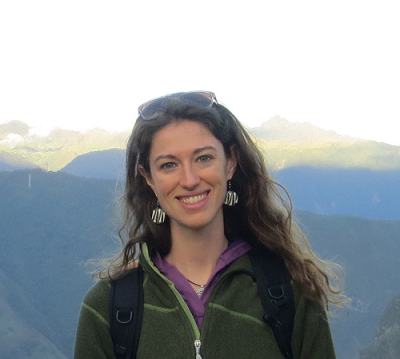

Wood, a research scientist and MS alumna in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS), has been working on TB research and prevention for over a decade in the lab of Dr. Jerry Cangelosi, a professor in DEOHS.

The team developed an oral swab technique that makes it much easier and less invasive to flag than the current gold-standard technique, which requires people to cough up sputum — a mucus-like substance — from their lungs. Their tongue swabs have up to 75% to 95% sensitivity at detecting cases in people showing symptoms of TB, compared to sputum analysis.

Recently, Wood and other lab members collaborated with the international consortium Regional Prospective Observational Research in Tuberculosis (RePORT) International to study how well the tongue-swab method detects cases among people with subclinical TB — some of those missing millions.

Stopping TB with a sample anyone can give

Wood and colleagues worked with RePORT South Africa to test both people symptomatic with TB — what researchers call clinical disease — and their household contacts who were asymptomatic and at risk for subclinical disease. They collected several samples from both cohorts, including tongue swabs, sputum and blood, in addition to chest X-rays.

They found that the tongue-swab method detected TB with 60% sensitivity in the clinical cohort and 34% sensitivity in the subclinical cohort.

Though the method was less sensitive in the subclinical cohort, “this is a group that would not have been tested otherwise,” Wood said.

With tongue swabs, she said, “we are testing a sample that can be collected from anyone, regardless of symptoms. This is a way of finding and treating [at least some of] the missing millions, which is critical to stopping the spread of TB and to interrupting transmission and reducing [the] overall burden.”

The method could help screen people for the disease in settings where it can spread in close quarters, such as workplaces and prisons. Renée Codsi, a PhD student in Cangelosi’s lab, is evaluating migrants’ and healthcare workers’ experiences of the tongue-swab method in reception centers for migrants in Italy and Spain.

Hope on World TB Day

March 24 is World TB Day, and Wood says it’s more important to shed light on the disease than ever. Though cuts to public health funding may intensify the disease’s spread, new research developments give her hope for efforts to fight it.

In the Cangelosi lab, researcher Alaina Olson recently reported two new analytical methods with improved sensitivity for detecting TB on tongue swabs. That study and another led by Wood were ranked as among the 139 most important papers of more than 10,000 TB publications in 2024 by the Tuberculosis Network European Trials (TBNET).

Using these high-sensitivity methods, Olson, Wood and UW Global Health Assistant Professor Adrienne Shapiro found improved sensitivity — 53% — among people who were living with HIV and at risk of also developing TB.

They did the work at the University of Witwatersrand (Wits) in South Africa, where one of the team’s collaborators, Lesley Scott, leads a team working on high-throughput methods for tongue-swab analysis.

Globally, there has also been general improvement in point-of-care devices allowing clinics to get quicker results from the swabs.

The team is hopeful that the World Health Organization will officially endorse oral swabs as a diagnostic sampling method for TB.

“That could be a real game changer in terms of global research and treatment and care,” Wood said.