Despite their invisibly small size, ultrafine particles have become a massive concern for air pollution experts. These tiny pollutants—typically spread through wildfire smoke, vehicle exhaust, industrial emissions and airplane fumes—can bypass some of the body’s built-in defenses, carrying toxins to every organ or burrowing deep in the lungs.

New research from the UW found that those effects aren’t felt equitably in Seattle. The most comprehensive study yet of long-term ultrafine particle exposure found that concentrations of this tiny pollutant reflect the city’s decades-old racial and economic divides.

The study, published July 5 in Environmental Health Perspectives, also found that racial and socioeconomic disparities in ultrafine particle (UFP) exposure are larger than those observed in more commonly studied pollutants, like fine particles (PM 2.5) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2).

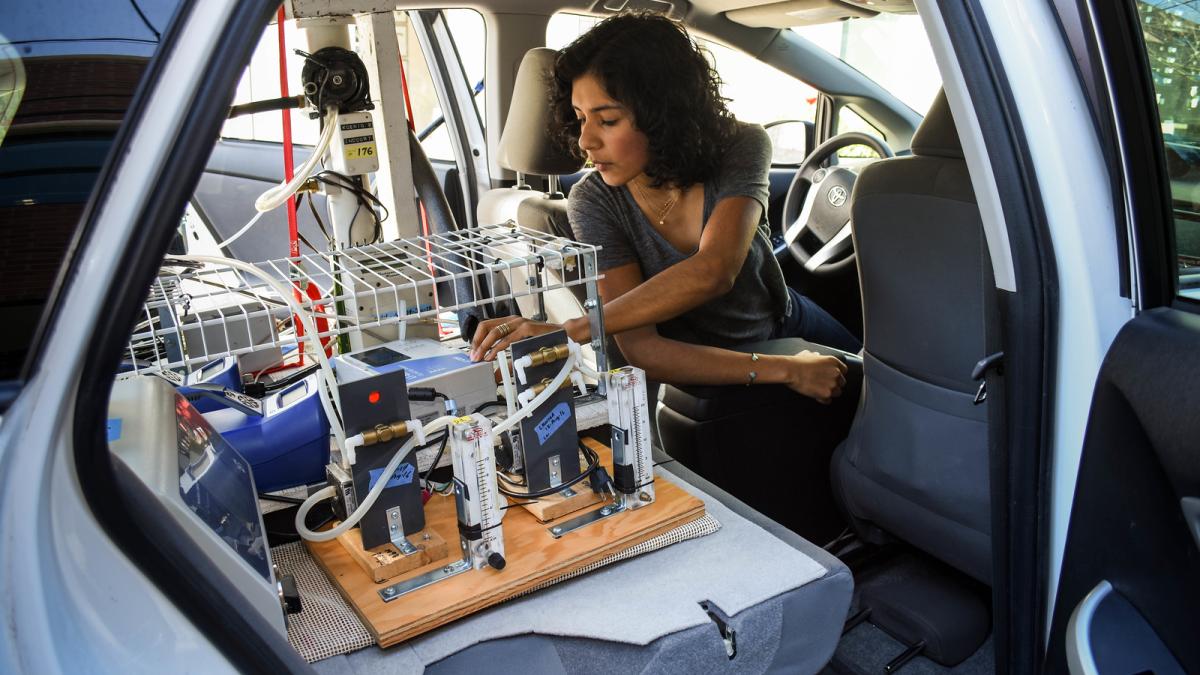

The study used mobile monitoring—a car loaded with air pollution sensors driving around the city for the better part of a year—to examine long-term average levels of four pollutants: soot (or black carbon), PM 2.5, NO2 and ultrafine particles. Researchers found the highest concentrations of all four pollutants on census blocks with median household incomes under $20,000 and those with proportionately larger Black populations.

Disparities in concentrations of ultrafine particles—which are less than 0.1 micron in diameter, or 700 times thinner than the width of a single human hair—were especially stark. Blocks with median incomes under $20,000 had long-term UFP concentrations 40% higher than average. Blocks where median incomes are over $110,000, meanwhile, saw UFP concentrations 16% lower than average.

“We found greater disparities with this pollutant of emerging interest, a pollutant that hasn’t been well-characterized. That’s very interesting,” said senior author Lianne Sheppard, professor in the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS). “Our work has shown the highest ultrafine particle concentrations are north of the airport and below common aircraft landing paths, downtown, and south of downtown where there are port and other industrial activities.”

Air pollution disparities a remnant of Seattle’s redlining

The study also found that modern-day air pollution disparities mirror Seattle’s history of redlining, the racist practice that denied racial minorities and low-income residents access to bank loans, homeownership and other wealth-building opportunities in more “desirable” areas. The practice shaped American cities throughout the early 20th century, building a foundation of segregation and environmental racism.

“These results are important because air pollution exposure has been shown to lead to detrimental health effects, and these health effects disproportionately impact racialized and low-income communities,” said Kaya Bramble, the study’s lead author, who graduated from the UW in 2022 with a degree in industrial and systems engineering. “Notably, air pollution is just one factor, and there are plenty of other examples of how systemic racism is detrimental to people’s health and well-being.”

Bramble proposed and carried out this study for the Supporting Undergraduate Research Experiences in Environmental Health (SURE-EH) grant program, which provides National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences funding and mentorship to undergraduates from underrepresented backgrounds to pursue research. She joined the program in June 2020 under Sheppard’s mentorship.

Other UW authors are Magali Blanco, Annie Doubleday and Amanda Gassett of DEOHS, Anjum Hajat of the Department of Epidemiology and Julian Marshall of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

Read the full release at UW News.