Editor's note: This study, which ended in 2019, found that communities underneath and downwind of jets landing at Sea-Tac Airport are exposed to a type of ultrafine particle pollution that is distinctly associated with aircraft. The study was the first to identify the unique "signature" of aircraft emissions in Washington and led to follow-up studies that are examining the health effects of this exposure in Washington classrooms. Learn more about the study

J.C. Harris lives on a cul-de-sac directly in the flight path of Sea-Tac International Airport’s third runway. For Harris, a University of Washington study analyzing air traffic’s impact on air quality in communities near and below Sea-Tac flight paths is far from academic.

The 58-year-old is concerned about the health effects on his neighborhood of increased flight volume at Sea-Tac, one of the nation’s fastest-growing airports.

“There’s a line of schools in the path of runway one where kids are out playing,” said Harris, a longtime Des Moines resident. “So what are they getting exposed to out there?”

Edmund Seto, associate professor in the UW Department of Environmental & Occupational Health Sciences (DEOHS), says community concerns like these led state lawmakers to commission a two-year study led by a team of UW researchers called the Mobile ObserVations of Ultrafine Particles study.

Seto is the study’s co-principal investigator along with Timothy Larson, professor in DEOHS and in the UW Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering.

First study to track air traffic pollution around Sea-Tac

The communities around Sea-Tac airport are not alone in their concerns about aircraft emissions.

Last week, US Congressman Adam Smith (D-WA) reintroduced a bill to establish a national study on the health effects of ultrafine particles around airport communities, including those in Seattle. The DEOHS study could help inform the legislation.

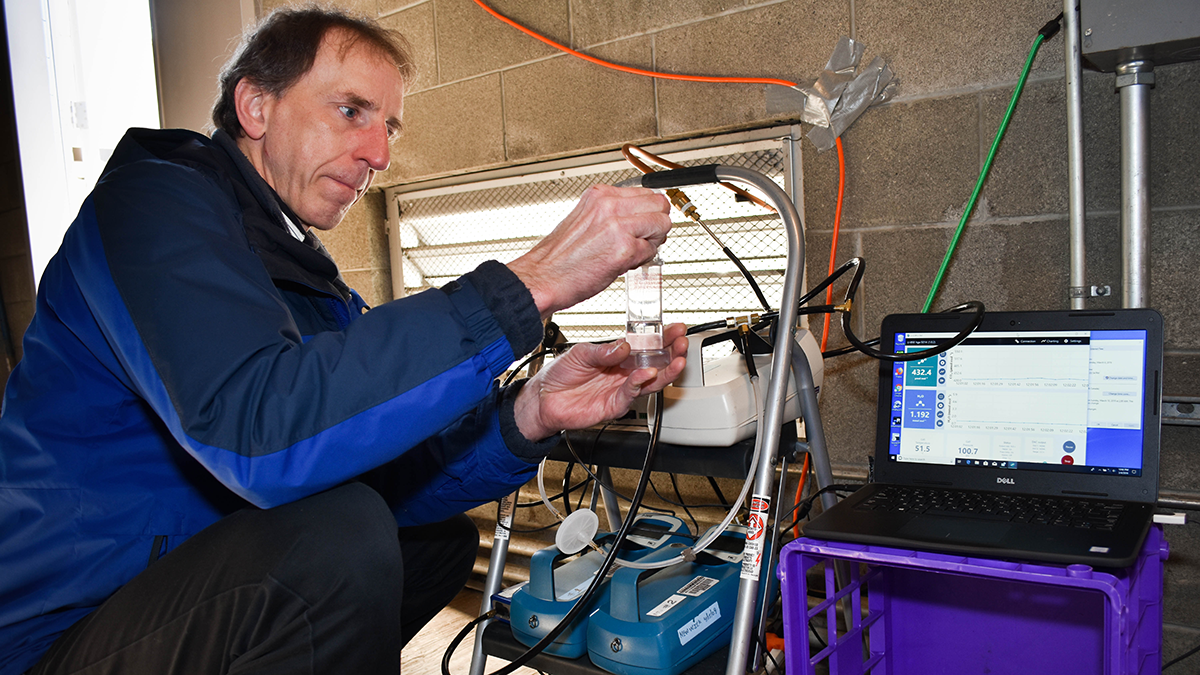

DEOHS researchers are measuring the geographic reach of aircraft-related air pollution exposures, distinguishing ultrafine particle emissions from aircraft versus those from cars and trucks.

They are also studying ultrafine particle levels in areas with high air traffic compared with areas not impacted by flights. Researchers expect to share initial findings this summer, with final results expected in December.

To Seto’s knowledge, this is the first study to systematically track aircraft-related air pollution in the communities around Sea-Tac, monitoring within 10 miles of the airport in the direction of flight paths.

It’s also one of the first to disentangle aircraft- versus road-related ultrafine particle emissions.

Ultrafine particles and air quality

UW researchers worked on an earlier Los Angeles International Airport study that found aircraft landings produced ultrafine particle pollution roughly equivalent to LA’s freeway network.

That pollution negatively impacted air quality much farther (over a 23-square-mile area that extended 10 miles downwind) than reported in prior airport studies. Seto said early analysis of data collected in the Sea-Tac study suggest there are elevated ultrafine particle levels along aircraft pathways.

What is the health effect?

Ultrafine particle exposure has been linked with adverse cardiovascular and respiratory health effects (and even possibly the risk of dementia). Yet the US Environmental Protection Agency does not routinely monitor ultrafine particle air pollution, Seto said.

The study wasn’t designed to capture health effects, but it laid the foundation for the Healthy Air, Healthy Schools project, led by DEOHS, to examine the impacts of improving air quality in Washington schools. It also sparked a UW proposal to design and evaluate new air filters for personal use or for buildings that might help reduce exposures to particles associated with aircraft.

The filters would make possible new studies that could demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship between the particles associated with aircraft emissions and short-term, acute health effects like inflammation and respiratory impacts.

Communities shape the research

For Seto, the study is “addressing on-the-ground needs with actionable research.”

Communities around Sea-Tac have shaped the research in concrete ways. The initial study design included mobile monitoring only (a cost-effective approach where researchers drive air monitoring equipment to myriad locations) and only during daytime hours. Community feedback led researchers to add monitoring at fixed sites, allowing the team to gather data day and night.

Community input also encouraged researchers to include Federal Aviation Administration flight data to analyze the relationship between ultrafine particle counts and flight traffic volume and patterns—important because of concern over increased flights in this region, Seto said.

“It’s about measuring in the right place at the right time under conditions people think are most representative of the issue,” he said.

“I want transparency”

Bottom line, Seto said: “When we’ve heard from residents, it’s often framed from an environmental justice perspective—why are flights concentrated over certain communities and not others?"

Those communities are asking legitimate questions about how this translates into differences in exposures and impacts and how health outcomes might be related to aircraft emissions, he said.

Harris hopes the study and its baseline data will help spur regular public monitoring of ultrafine particles—and a study of what the numbers mean for the health of impacted communities.

“I want us all to be able to see the air-quality impact of the number of flights growing and flight patterns changing,” he said. “I want transparency.”